Illegal arson and civil resistance in Rosario, Argentina

By Eva Youkhana and Francisco Preiti*

Rosario, February 2023. We return from Cordoba, the second largest city in the center of Argentina where we paid a visit to one of the nine global Right Livelihood Campuses. We also met with Raul Montenegro, an RLC – laureate who won the “Alternative Nobel Prize” (Right Livelihood Award) in 2004 for his work with local communities and indigenous people to protect the environment. The journey leads through the seemingly eternal pampas of Argentina and passes Rosario, a city 280 kilometers north of Argentina’s Capital Buenos Aires.

We can hardly breathe during our car trip, although the windows are tightly closed, because a cloud of smoke spreads out and accompanies us for at least an hour. The city is wrapped in fire while it is incredibly hot and dry. A heat wave has gripped this part of South America, lasting several months from November 2022 to March 2023 and keeping the entire country in suspense. Around us we see dead cattle stretching on all fours and lifelessly adorning the surreal landscape.

Argentina’s exceptional heat wave

According to the Argentine Weather Service in February 2023, the high temperatures especially affected the center of the country (Buenos Aires, La Pampa), the Litoral (Entre Ríos, Corrientes), and the Cuyo region (Mendoza and San Luis). The highest temperatures since 1961 were recorded in the Capital of Buenos Aires. It was 38.1 degrees Celsius during the day, and the temperatures remained very high even at night with stable 30 degrees Celsius. These nights were said to be “the warmest in the last 60 years”. This record was replicated in Rosario, Argentina’s third largest city, counting 1.3 million inhabitants. It is located in the Province of Santa Fe, Argentina’s central ‘Mesopotamia’ region. It lies between two huge rivers, the Paraná and Paraguay Rivers, in the middle of a delta with 5,600,000 hectares of wetlands. The region has been attractive for agriculture and livestock because of its extremely fertile soils since the colonization by the Spanish. It therefore still is the country’s main area for industrial agricultural and livestock production.

Rosario: Famous past, furious present

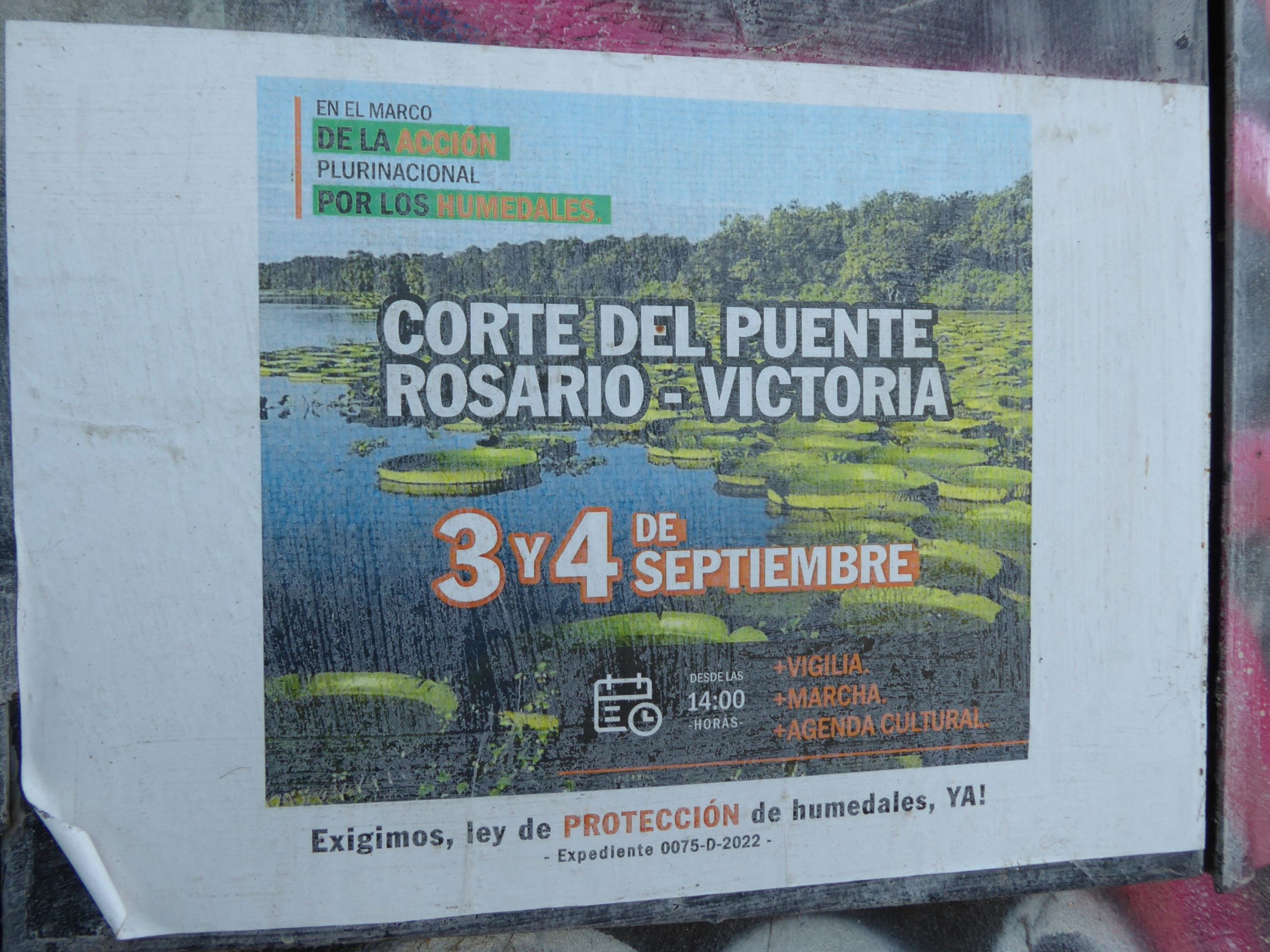

Rosario is also the birthplace of the revolutionary Che Guevara and soccer player Lionel Messi and known as the “Cradle of the Flag”, as the Argentine national flag was hoisted there for the first time in 1812. A monument honoring this event, the Monumento a la Bandera, completed in 1957, is an emblematic and symbolic construction for the national state. But, it also is site of numerous official, civic, and protest acts such as marches and demonstrations. Unfortunately, Rosario is also the epicenter of the wetland fires, which have reached uncontrollable size since 2020, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic. Moreover, the fires have provoked unprecedented protests by manifold environmental movements.

Since colonial times, natural land has been transformed on a large scale. There is even a special name for this landscape transformation: The ‘pampeanization’ of the wetlands. It is kind of a historical given and therefore rarely questioned. For this reason, fires are set repeatedly to gain new land for human activities such as cattle herding, creating new cropland but also intensive agriculture, and even construction, as the city of Rosario is expanding.

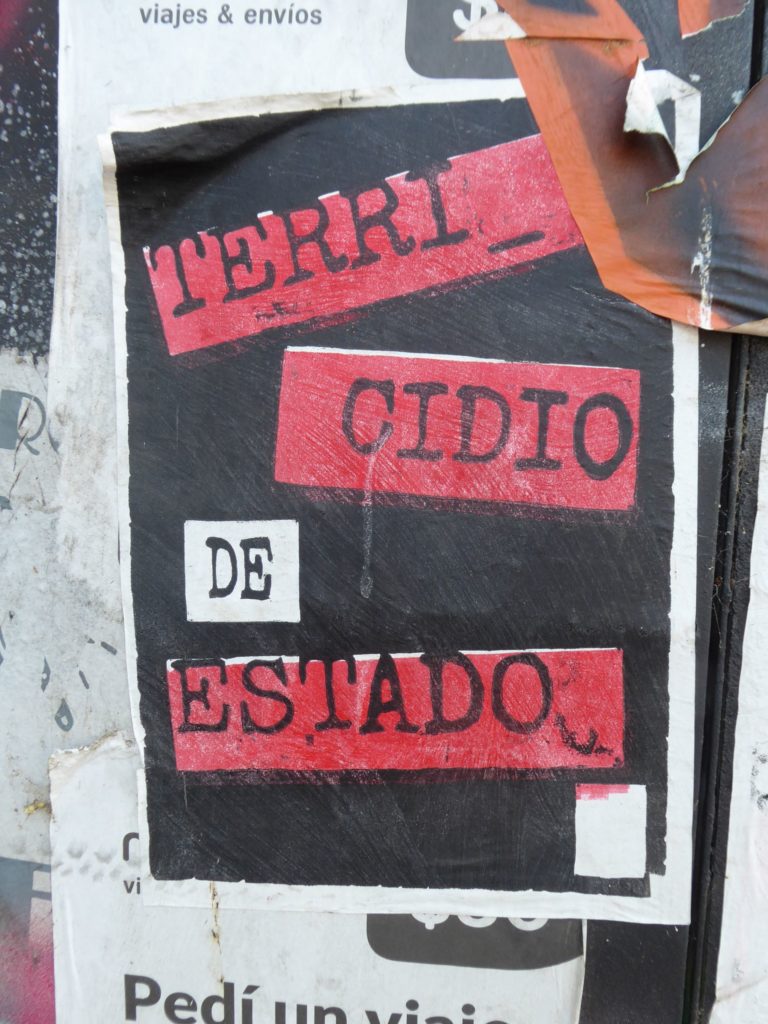

However, most of the burning of the wetlands is due to illegal arson that plagues the whole country and continent. Besides the Argentine wetlands Fires, fires are destroying large areas of the Gran Chaco and the Amazon region. In each of these environments, the dynamics are similar: agricultural companies intentionally burn supposedly ‘unused’ land to later buy it up at knock-down prices for cattle ranching or soybean production.

The soy boom in the late 1990s and the growth of the cattle industry triggered by increasing global demand for meat have contributed to getting these fires out of control altogether. Flora and fauna as well as the population in the surrounding areas are affected to such an extent that stricter legislation is needed to protect the wetlands. Yet, these floodplains host a biodiversity that produces unique landscapes. Thus, the fires pose an additional threat to the resilience of native species. In addition to the fires, the wetlands are under stress from droughts and further impacts of climate change.

Making a difference: Environmental and civil movements in Rosario

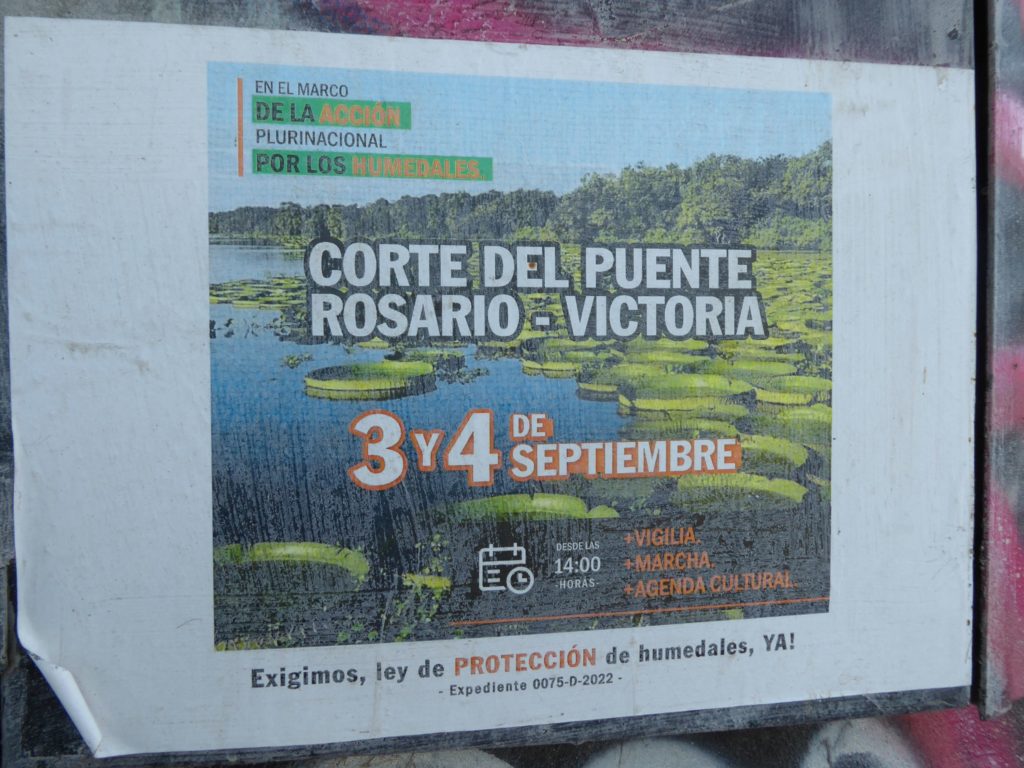

The environmental movement in Rosario, which has gained momentum since 2020, comprises a variety of heterogeneous actors ranging from citizens, university students, left-wing political groups, conservationist activists and feminists. They all are attracting attention with massive acts of protests by which they express a repertory of new ‘languages of valuation’. The demands of the environmental activists are clear: stricter legislation for the protection of wetlands and more consistent punishment of illegal arson.

These demands are creatively staged, with people and things merging into collective protest assemblages. For example, the feminist art collective Thigra regularly organizes acts of protest to position heterogeneous actors against the so-called ecocide. In the protest “Tu fuego es complice” staged in November 2020, more than 200 people participated in a human chain with buckets of water to extinguish the fire in the National Monument (see photo below), which stands for freedom and Argentina’s independence.

By this, the collective wanted to sensitize to the state’s and municipal administration’s responsibility, which seem to ignore the problem deliberately. Break-neck actions such as attempts to extinguish the fires on the island are regularly undertaken by people therewith risking their lives. Especially when the fires spread to the houses of the islanders, while the city administration and the state stand idly by.

The citizens and activists are also fighting against the commodification of nature. They question the official discourses that pursue an eco-efficient idea of development putting the services of the natural system (ecosystem services) at the center stage. In this contestation, the Rosario Victoria Bridge, the large cargo ships navigating the Paraná River, and the fire on the islands, are becoming symbols of the exploitation and extraction of the ecosystems’ natural resources.

Twenty years after Raul Montenegro was awarded the Alternative Nobel Prize, ecosystems in Argentina and throughout South America are under threat. So, these everyday protests of the affected population are all the more important. Their creative protests exemplify that resistance practices can be collectively organized, while new sources for alternative ideas of knowledge production and concepts of life can be created.

*Eva Youkhana is Acting Director at ZEF and spending a sabbatical term in Argentina. Read more about her sabbatical on ZEF’s website here.

Francisco Preiti is an Assistant Professor at the National University of Rosario (Contact: franciskojose03@gmail.com).