Living landscapes as cultural heritage in East Africa: preserving the past and building sustainable futures

This blog post takes you to the Konso Cultural Landscape, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, in Ethiopia.

When we started our trip to visit our partner university in Dilla, southern Ethiopia, on July 23, 2024, we had no idea that the largest landslide ever recorded in Ethiopia had just taken place just a few kilometers away from Dilla. At least 264 people died in the mountainous Gofa zone, according to the latest count, following heavy torrential rainfall that lasted for days, affecting the whole of southern Ethiopia. Although heavy rains during the rainy season are not uncommon in this region, the devastating extreme weather event with fatal consequences can definitely be attributed to the effects of climate change. On arrival in Dilla, our colleagues were still on-site and involved in disaster management. The impacts of this calamity, costing many lives and destroying villages and hopes, will be with us for a long time to come.

Ethiopia is one of the riskiest countries when it comes to the consequences of climate change and natural disasters such as floods and droughts. The second most populous country in East Africa (with over 125 million inhabitants) is topographically very diverse. Large parts of the population live in remote and rural areas, where they are largely isolated from the infrastructure. This makes the situation even more precarious and responses slow.

Role of local dynamics at UNESCO world heritage sites

This is precisely where the Volkswagen Foundation-funded project “Local Dynamics and Integration of UNESCO World Heritage Sites of Outstanding Universal Value: Evidence from Cultural Landscapes in Ethiopia and Kenya” comes in. The project is working on the impact that global change has on the living landscapes and livelihoods in two selected UNESCO cultural heritage sites: The Konso Cultural Landscape in Ethiopia and the Sacred Mijikenda Kaya Forests in Kenya. Both sites are of “outstanding universal value” according to UNESCO. The research is carried out in cooperation with staff and post-doctoral researchers from Dilla University in Ethiopia and Kenyatta University in Kenya. This interdisciplinary team investigates local dynamics in which different interests and power asymmetries are expressed and traditional ways of life have to withstand the pressure of a transforming reality.

A core event of our visit was the project’s international mid-term conference which was held on July 25, 2024. It was organized and prepared by the local project coordinator Dr Abiyot Legesse and his team and also by Dr Girma Kelboro Mensuro, the former coordinator of the project at ZEF. The program included visits to various research areas, added by the presentation and discussion of theoretical approaches and preliminary results of the field research. As a result, the travel team with the newly appointed ZEF coordinator Asrat Gella, Dr Till Stellmacher and Dr Eva Youkhana were able to gain an excellent insight into the beauty of the landscape and life in Konso, as well as the risks and challenges for the local population.

After all, the status of being a “World Heritage Site” is not only associated with fame, but also exposes the population to enormous pressure and responsibility. The international visibility attracts attention and requires measures to preserve the cultural enterprise. As this not only comes across as a material asset, but also displays immaterial goods in the form of a very specific livelihood, the question arises as to how something that is in constant movement and transformation can be preserved in its original form at all.

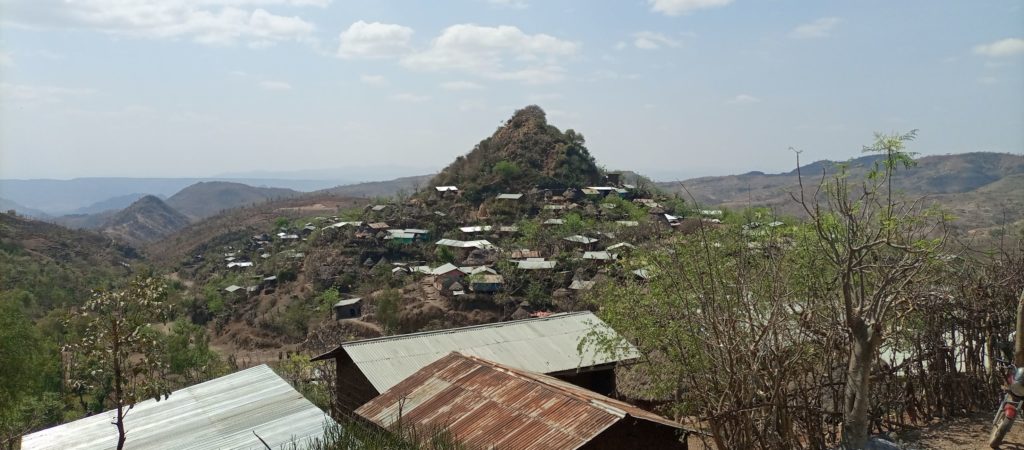

Setting: Konso Cultural Landscape

Inscribed into the World Heritage List in 2011, the Konso Cultural Landscapes are predominately composed of an extensive network of dry stone terraces both in and around farmland and settlements. The terraces in the farmlands serve to conserve the soil from erosion while the network of terraces in and around settlements serve as fortification. Part of the inscribed properties also include sacred protected forests that have been preserved for generations in their natural state. It is not known as to when the terraces were built and when the sacred forests were established; they are instead attributed to be the work of ancestors long gone. All of these features of the Konso Cultural Landscapes are products of the social and cultural organization of Konso society and its uniquely intricate system of local governance. But with increasing population density, the ever-increasing encroachment of formal state authority structures and the resulting decline of traditional authority structures, as well as the increasingly more visible presence of evangelical Christianity, the Konso way of life and its unique landscape are increasingly coming under pressure from both local and global processes.

Given a strong population growth and Konso’s dry arid climate, it is not likely that the traditional terraced agriculture that has sustained the population for eons will continue to be a viable means of livelihood for all. But alternative sources of income and livelihood are limited and can only be found sporadically in tourism, and usually only for a handful of people who offer themselves as tour guides or are involved in the production of handicrafts. The majority of the mainly young population has little chance of a better or more profitable life. This has even led to the proliferation of theft of local cultural artifacts such as wooden grave statues (waka) which are increasingly being offered for selling to tourists in an illicit trade. The small local museum is full of waka statues that have been recovered after they were stolen from sacred burial forests and local community centers called poqollas.

On the ground: Visiting local communities

The appearance of the villages we visited speaks volumes about the current state of things. It is mainly the old people and children who welcome every guest with joy and then, depending on the situation, offer handicrafts or stage an impromptu cultural dance. Our visit to the walled village of Gamole, which is a special attraction due to its centuries-old construction of mud huts and ramparts made of stone and wood, as well as its impressive network of stonewall fortifications, did not present us with an impression of a thriving community.

Whilst a select group of men and women happily performed a courtship dance, and bravely included the ferenjis (foreign guests) in the dance, the loud speakers from the nearby evangelical church boomed with the aggressive preaching of a pastor. We were unable to understand the messages but the tone was unmistakably hostile. And this was only one of many evangelical churches we encountered in the area, many of which are funded by evangelical missions based in the US. These fundamentalist evangelical churches have little, if any, regard for the Konso way of life or its cultural traditions; labelling native forms of faith and even cultural practices and traditions as unworthy, eternally outdated, or even sinful.

During our visit we paid special attention to the situation of women and children. While Ethiopian society, and rural Ethiopia in particular, is a very patriarchal country, traditional gender relations appear to be subject to a particular stress test in Konso. The traditional governance structure composed of generational strata and the clan-based authority structures with clan chiefs at the top give women no chance to be involved or have a say in the way their communities are administered. We also understood from our conversations with community members that women are usually not understood to have formal property ownership to assets such as land; even though these rights are to be extended to them through the ownership rights of their husbands. This has created tensions in the current drive of the government to issue formal certificates of land-use rights in the area. While these certificates have been issued to farmers in much of the central highlands and the northern parts of Ethiopia for years now, the effort is only starting here in the south. Already, it is being contested by Konso’s men and clan chiefs who object to this “formalization” of land rights.

Outlook

How can these emerging challenges, some unique to the local reality and some extensions of global changes, be accommodated and addressed without threatening the unique history, culture, tradition and way of life of the Konso who produced the unique landscapes that have been recognized as sites of universal human value? The project “Local dynamics of UNESCO world heritage sites” looks into this question and aims to explore ways in which the local dynamics of heritage sites can better be understood and integrated into UNESCO criteria and working procedures and calls for a wider realization of the need to approach these sites as “living” landscapes.

Authors: Asrat Gella, project coordinator and Eva Youkhana, PD at Bonn University and senior researcher/group leader at ZEF.

The research project “Local Dynamics and Integration of UNESCO World Heritage Sites of Outstanding Universal Value: Evidence from Cultural Landscapes in Ethiopia and Kenya” is funded by a generous grant from the Volkswagen Foundation.