Immersive learning: Engaging with the realities of Nairobi’s informal settlement Korogocho

Engaging in fieldwork is multifaceted, fraught with unique challenges and rewarding insights. I conducted my field research in Nairobi’s informal settlements Korogocho and Pumwani-Majengo because I wanted to understand the everyday dynamics around green space governance. My field study in Kenya’s capital was split up in two phases: The first phase took place from August 1, 2023 to January 31, 2024, and the second one from June 18, 2024 to August 18, 2024.

Bridging academia and real-world challenges

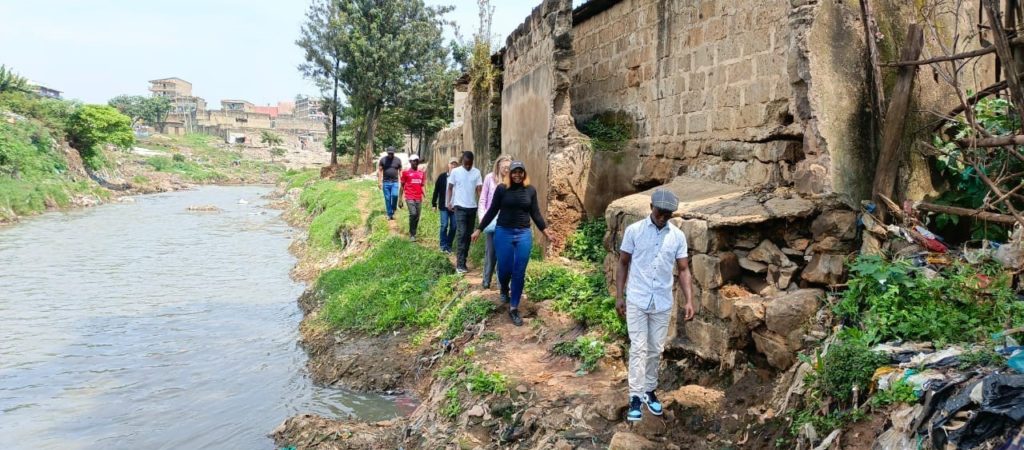

On July 21, 2024, I hosted my supervisor, Professor Detlef Müller-Mahn, along with his collaborative partner, Professor Jessica Budds in Korogocho, one of the study areas in my doctoral research. During their visit, we conducted a transect walk, engaged in informal discussions, made personal observations, and held a debriefing session to address emerging issues. This hands-on approach allowed us to observe the living conditions, interact with residents, and gain deeper insights into their daily lives and struggles. Later in the month, we extended this experiential learning opportunity to Masters students from our collaborative program.

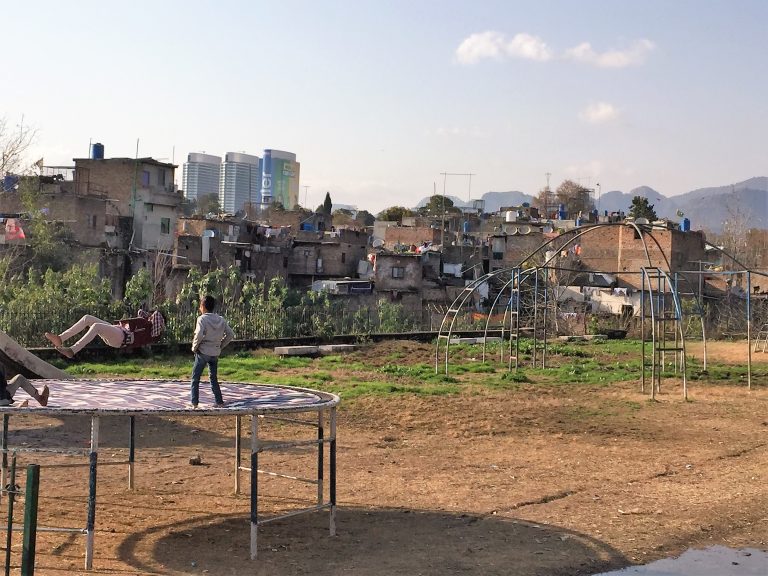

On July 28, I also hosted 30 Master’s students at the Korogocho informal settlement. With the assistance of a local youth group, we conducted a transect walk along the Nairobi River, which runs through the Korogocho villages. This walk provided the students with a direct view of the settlement’s layout, infrastructure, and environmental challenges.

Throughout the walk, we engaged in informal discussions with community members, gaining valuable insights into the socio-economic dynamics of Korogocho. Many of the students, primarily from Germany and unfamiliar with informal settlements, experienced a range of emotions, including sadness and helplessness. They were particularly struck by the severe lack of basic infrastructure, high levels of poverty, recent demolitions and evictions, and the sight of the Dandora dumpsite. This dumpsite, the largest in Kenya, serves as a critical survival resource for 70% of the community, highlighting its global connection as it receives waste not only from around Kenya but also from across the world. During a later debrief session, the students shared their reflections and discussed their experiences from the fieldwork.

Insights into power structures and urban land politics

Our fieldwork in Korogocho unveiled four critical aspects of urban land politics and the broader socio-environmental challenges that informal settlements face:

- Power structures and urban land politics

In Korogocho, the struggle for land is deeply rooted in complex power structures. We observed that Korogocho is frequently marginalized in urban planning processes, with land allocation often influenced by political affiliations and economic power rather than community needs. This skewed distribution perpetuates poverty and entrenches the political disenfranchisement of residents.

The transect walk along the Nairobi River, which flows through Korogocho villages, vividly illustrates this. The river, a vital water resource, is polluted and poorly managed, reflecting broader patterns of environmental injustice. These communities bear the brunt of environmental degradation, while wealthier, even amongst the residents, and the politically connected groups control land and resources.

2. Economic dependency and environmental degradation: The Dandora dumpsite dilemma

Korogocho’s proximity to the Dandora dumpsite, the largest in Kenya, underscores the economic and environmental complexities faced by its residents. Residents rely on the dumpsite for their livelihoods, scavenging for recyclable materials in hazardous conditions. This economic dependency is a direct result of systemic neglect and the lack of sustainable employment opportunities. The proposed relocation of the dumpsite, driven by political and economic interests, threatens to displace these communities further, exacerbating their vulnerability. The students further observed that the dumpsite represents not just a local issue but a global one, as it handles waste from around the world. This global-local nexus highlights how neoliberal economic policies and global consumption patterns impact marginalized communities.

3. Global agenda and local realities

During our discussions, it became evident that global agendas were subtly influencing local narratives. We observed that community members were well-versed in contemporary topics like climate change and community hydroponics farms. They employed sophisticated terminology and subtly hinted at their need for funding, presenting their challenges in a manner tailored for potential donors. The community’s engagement with topics like climate change and hydroponics reflects the influence of global environmental discourse. This discourse often comes with specific funding priorities and development models that can shape local practices and priorities. The use of sophisticated terminology and framing of challenges to appeal to potential donors highlights the community’s strategic adaptation to these global narratives.

However, this adaptation has created a tension between local needs and global agendas. While aligning with global priorities might attract funding, it may also divert attention from pressing local issues that do not fit neatly into global frameworks. For instance, while climate change and hydroponics are important, the immediate concerns of basic infrastructure, sanitation, and livelihood security in Korogocho might be overshadowed.

4. The role of NGOs: Tokenism vs. genuine change

Local Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) are often viewed as agents of change in informal settlements, but our fieldwork revealed the limitations and unintended consequences of their interventions. Students observed that some NGOs’ efforts to “green” the settlements and improve living conditions can inadvertently reinforce disempowerment. While these initiatives are well-intentioned, they sometimes offer superficial solutions that fail to address the root causes of poverty and environmental degradation. The presence of NGOs has also created dependency on external aid, undermining local agency and self-sufficiency. Genuine empowerment requires a shift in power dynamics, allowing communities to lead their development agendas and advocate for systemic changes.

Youth groups: Agents of change in land politics?

Youth groups in Korogocho play a crucial role in challenging existing power structures and advocating for equitable land governance. These groups are at the forefront of political and environmental activism, pushing for transparency, accountability, and inclusivity in urban planning processes. Their involvement underscores the importance of grassroots movements in advancing social and environmental justice. However, they face significant resistance from established political interests that benefit from the current power dynamics. Additionally, internal conflicts arise as youth groups and individuals may have their stakes in land use, control, and ownership. This internal complexity adds another layer of difficulty to achieving comprehensive and fair land governance in informal settlements.

Author: Valentine Opanga, junior researcher at ZEF.

Valentine’s research is funded by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD)