Eschew obfuscation (write so that people can understand what you want to say)

This blog post was written by Cory Whitney and Anna Yuwen

“The pen is mightier than the sword” (Bulwer-Lytton, 1896) is the age-old adage that highlights the power of writing. But if writing becomes muddled and unclear, does its power begin to fade? The adage emphasizes the value of communication: language that is inaccessible tends to discourage open dialogue rather than foster it. As academics and scholars, many of us are dedicated to demystifying the world around us and sharing knowledge with others. Doing so with more clarity can benefit us all.

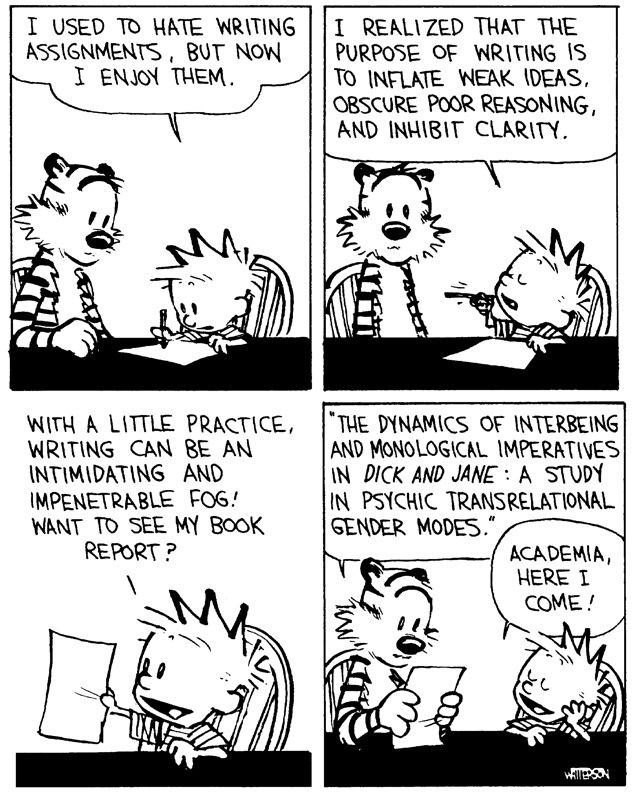

If you pick up any academic book or paper, you inevitably come across clumsy, awkward or outright pretentious writing. As part of our academic training we can sometimes learn to hide what we want to say (Watterson, 2009) and end up replacing accessible language with jargon-laden terms.

This blog pos t is written with academic writers in mind, many of whom struggle with scholarly writing (us included). We’ve outlined some of our ideas here, but keep in mind that there is no single formula for good writing. Writing and language are inherently multifaceted and capable of so much, including humor, passion and irony. Writing can encompass extremes, from being overt and explicit to subtle and expressive. Whatever our intentions, we could all use some support to write more effectively. As academics we should write with the awareness that the more clear and concise our academic work is, the more likely it is to be read and cited.

t is written with academic writers in mind, many of whom struggle with scholarly writing (us included). We’ve outlined some of our ideas here, but keep in mind that there is no single formula for good writing. Writing and language are inherently multifaceted and capable of so much, including humor, passion and irony. Writing can encompass extremes, from being overt and explicit to subtle and expressive. Whatever our intentions, we could all use some support to write more effectively. As academics we should write with the awareness that the more clear and concise our academic work is, the more likely it is to be read and cited.

“Bad” academic writing is not always a bad thing. Our writings are sometimes filled with academic concepts and unique terminology because of the abstract nature of our work. There are infinite intersections within any one particular line of inquiry. In this way, “bad” academic writing can be seen as a mirror of the complexity of real life systems. Sometimes writing abstractly can be useful in attracting readers and getting them to take the time to carefully read a text. Defenders of bad writing tend to argue that it represents the struggle of dealing with complex concepts and ideas (Culler et al., 2003). Many social scientists, such as Judith Butler, reject the demand for good, clear writing. They believe the demand for good writing to be the pinnacle of ignorance. In defense of “bad” writing, Butler claims:

“What does it say about me when I insist that the only knowledge I will validate is one that appears in a form that is familiar to me, that answers my need for familiarity, that does not make me pass through what is isolating, estranging, difficult, and demanding?” (Butler, 2003)

Bad writing also has the potential to disrupt expectations, specifically through the use of non-conventional language and style. This can make readers feel uncomfortable and even alienated, and that can be quite useful: the discomfort that we feel can lead us to think more critically about the text, to engage with it on a different level and form new insights. After all, as scholars, we should be open to engage with challenging concepts, question our worldview, and think about new perspectives.

Sometimes though, and probably most commonly, “bad” academic writing is the product of an academic writing culture that values a certain level of prestige and being overly complicated. Writers of all academic backgrounds are guilty of using academic vernacular, which can be both extremely precise and dense. Precise terminology eludes adequate definition, while dense terminology requires much more abstraction. And yet we continue to write this way because we believe this is what it takes to get ahead. We see others do it – even get away with it – so we imitate it. As writers we are shaped by our environment and can become so entrenched in jargon that we are nearly unable to speak about our work to anyone outside of our field. To overcome this we could try explaining our ideas to someone who is unfamiliar with the topic, programmers call this rubber duck debugging (Hunt and Thomas, 1999).

While it’s easy to point the finger at academic institutions, we also need to look at these learned behaviors and critically question why we continue to reproduce them. In that sense, inaccessible writing often manifests as a kind of academic posturing. We write badly because we are uncertain about our own ideas and hide behind a rhetorical style of “mystification that eludes criticism,” (Nussbaum, 1999) either because we make few definite or highly fragmented claims. Instead of being useful, this kind of academic writing can come across as as elitist. As Nietzsche once wrote:

“Those who know that they are profound strive for clarity. Those who would like to seem profound to the crowd strive for obscurity.” (Nietzsche, 1882)

Recommendations

We imagine that we can all write without support, that our thoughts and ideas should flow effortlessly onto the page. For most of us this is impossible. A piece of writing is necessarily something that has been picked apart and re-written many times before it is done.

Academic writing has certain demanding structural frameworks which may help facilitate understanding. Without an overarching structure, figuring out arguments and conclusions becomes laborious and obstructive to knowledge (re)production. The best way to prepare for this is to become familiar with the format that is preferred by your journal and follow it closely. This often means that you will need to tease apart the introduction, materials and methods, results, conclusions, and discussion.

Being curious and critical of our own writing can be a very helpful start to situating our writing in a larger context and making it readable. We should continually ask ourselves about our reasoning for pursuing any lines of inquiry. One of the foundations of academic and scientific writing is the continuous exchange of questioning and counter-argument. Our writing will be much better if we have a clear overview of the literature that disagrees with our theoretical and methodological approaches and know what these arguments are.

One piece of advise that we hear over and over again is to use active voice. Take ownership of your work. Instead of writing, ‘fieldwork was done in the month of January’ say ‘I did the fieldwork in January’. Likewise with choices for fieldwork and analysis, make it clear that is you or the authors that were the actors behind the work. While ambiguous prose has a place for certain types of academic writing, active voice communicates your ideas much more clearly and correctly.

There are many other simple rules that can make a world of difference for your writing and help save your co-authors and supervisors a lot of time and effort. Pick up a writing guide to help guide you in this writing journey. None are perfect, but the important thing is that you find one that you like. Read it and have it handy as a reference when you have issues. One of the most common guides for writing in English is by Strunk and White (Strunk and White, 2000). In it, they outline the basic rules of how to write plain English style and point out the most commonly violated rules of usage and composition. Good academic writing not only requires a good command of the language, but also a good understanding of how to frame complex ideas.

Finally, and most importantly, READ! Read papers, books and essays inside and outside of your academic fields. We should familiarize ourselves with a variety of academic writing styles and be connoisseurs of writers who use language in a way that we enjoy. The more we read, the better our writing will be.

References

Hunt, A., Thomas, D., 1999. The pragmatic programmer. Addison Wesley, Boston.

Nietzsche, F.W., 1882. Die fröhliche Wissenschaft. Verlag von Ernst Schmeitzner, Chemnitz.

Nussbaum, M., 1999. The professor of parody. New Repub. 22, 37–45.

Strunk, W., White, E.B., 2000. The Elements of Style. Longman, New York.

Thank you for this concise guide to academic writing. It is helpful to have this advice and these resources in one place. I will take your advice into my writing.