Beyond the Skyline: Collective Memory in Bogotá’s Largest Self-Constructed Settlement

Blog by Clement Roux, Eva Youkhana and Christian Petersheim

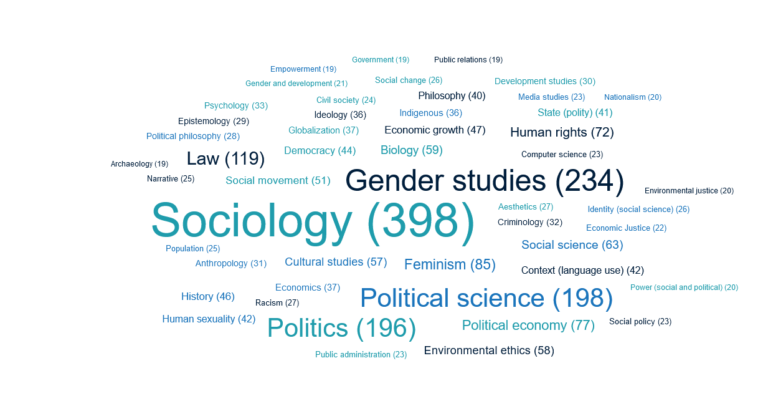

Bogotá, November, 2024. During our research stay in Colombia’s capital we took the opportunity to visit the Museo de la ciudad autoconstruida (MCA), or the Museum of the Self-Constructed City, located in the district of Ciudad Bolivar. To get there, we took the gondola lift, which has been in operation since late 2018. The gondola system was built as a complementary transportation service to the Transmilenio (Bogotá’s bus rapid transit system built in 2000). It thus connects the poorer neighborhoods in the south (i.e., the Ciudad Bolivar district) with the central areas of the city (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/TransMiCable). The 3.34-kilometer gondola has four stations and can transport up to 7,000 people per day.

Ciudad Bolivar: One of Colombia’s and the world’s poorest settlements

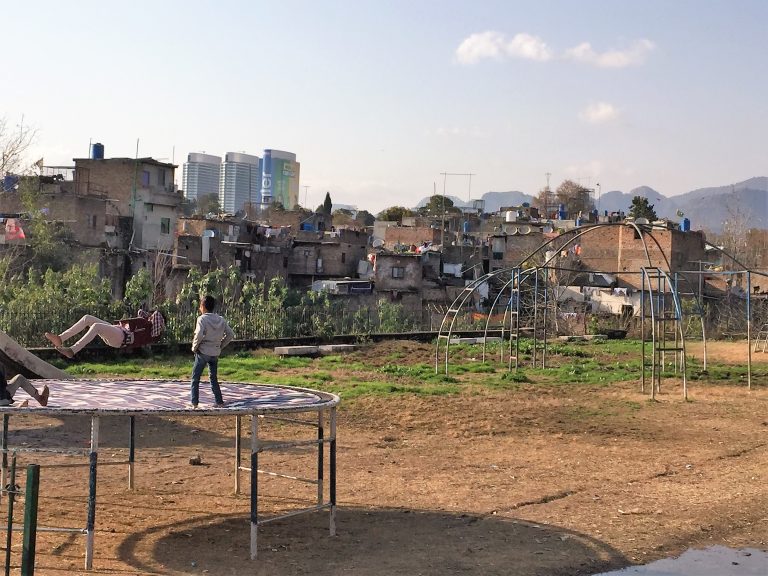

Ciudad Bolivar is the 19th district of the capital city of Bogotá. With more than 850,000 inhabitants (https://bogota.gov.co/mi-ciudad/localidades/ciudad-bolivar), two-thirds of whom belong to socioeconomic class 1 the most precarious of all classes (there are 6 in Colombia in total, into which all neighborhoods, right up to the richest class 6, are subdivided). This means that the neighborhood is one of the poorest residential areas in the Colombian capital. It is also one of the largest urban poverty settlements in the world. Due to the decades-long civil war, immigrants from the neighboring departments of Tolima and Boyacá in particular moved into what was then, and still is, a rural highland region.

Within a few years after the beginning of the armed conflict in the Mid 1960s, the population of Ciudad Bolivar had grown to 50,000. In the 1980s, the city began an urban planning phase that included the construction of additional residential areas with the help of the “Ciudad Bolivar Urbanization Plan” for the city and the Inter-American Development Bank. Today, Ciudad Bolivar is not only one of Bogotá’s largest neighborhoods, but it also possesses an incalculable natural, historical, and cultural wealth, manifested in a variety of landscapes, water sources, artistic expressions, heritage sites, and traditions.

Keeping the district livable: How inhabitants fought for their rights

To make this possible, the inhabitants have made great efforts and have had to fight hard for their rights to decent housing, access to land and water, and their right to the city. Since the first inhabitants settled, “…a general panorama of common elements has been revealed, such as the historical existence of the haciendas that made up the territory and the organizational processes for obtaining the basic elements of life, among others”, according to Lizarazo Guerrero and Sánchez Mojica (2019), two scientists from the ‘Corporación Universitaria Minuto de Dios’ (UNIMINUTO) who presented a study on the history of Ciudad Bolivar.

When drug trafficking from Medellín arrived here in the 1980s, violent confrontations between smugglers from different sectors, such as cocaine and emeralds, became more frequent (ibid.). But despite the constant growth of criminal groups and practices, processes of communitization and collective action have been implemented with visible success.

A walk through El Paraíso, the urban area at the end of the TransMilCable, gives the impression of a well-kept and popular neighborhood. The houses are in good condition. A large number of them are decorated with murals, testimony of the daily life of its inhabitants. This can be appreciated during a walk along the promenade “Malecón”, which is located at an altitude of 2,825 meters. It offers a breathtaking view of all of Bogotá. The murals depict the people living nearby: a woman working at her sewing machine, a young man skateboarding through the streets, or a cyclist with pink hair and baggy summer clothes. The idea is to show the diversity of the residents and celebrate their coexistence. On weekends, passersby report that this promenade is filled with families, couples and children who take advantage of the common space and excellent views to spend time together outdoors. There is little to indicate the hard work of the residents.

Visit to the amazing Museum of the Self-Constructed City

A visit to the Museo de la ciudad autoconstruida, or the Museum of the Self-Constructed City illustrates the collective efforts and forms of protest for the right to the city, self-management, and a dignified life for all. Many groups are represented here: the elderly, who were the first settlers and benefit from many free activities, African-Colombians, indigenous people from different nations, youth, etc.

Conceived at the same time as the gondola system in late 2018, the museum is both a self-governing community gathering place and a showcase for curation that challenges stereotypes about the neighborhood. The former is the result of a consultative process that determined how the community itself wanted to tell its own story.

Ciudad Bolivar’s 1993 “Citizens’ Strike” (Paro Cívico) is at the center of this collective memory. Tired of seeing their living conditions deteriorate, hundreds of Ciudad Bolivar residents blocked the city’s main access roads until the administration agreed to discuss with them a list of demands drawn up in advance during community meetings. After a few clashes, the municipality accepted almost all of the demands, and popular commissions were created to follow up on the signed agreement, constructing a dynamic tradition of social struggle for the right to the city in Bogotá that continues to this day (Mauro Armando, 2019).

What’s most striking about El Paraiso is the way the community has taken ownership of the museum and taken care of it. Or as Claudia Godoy Linero, Director of the tourism network ‘Conoce Magdalena’ puts it in her essay on tourism:

“El Paraiso in Ciudad Bolivar is more than a tourist destination. It is a symbol of change and hope. From the colorful graffiti to the warmth of its people, this place invites you to rediscover Bogotá from a different perspective and celebrate the strength of a community that knows how to turn adversity into opportunity. If you’ve ever wondered what lies beyond the heart of the capital, take the plunge and explore the highlands of Ciudad Bolivar and discover the true meaning of resilience”. (https://conocemagdalena.com/el-paraiso-de-ciudad-bolivar-redescubre-bogota-desde-las-alturas/).

“But be careful not to romanticize poverty,” warns Daniel Felipe Zapata, a 30-year-old cultural mediator who has worked at the museum since it opened in 2021. “There is nothing enviable about living in these precarious buildings, made of cheap materials and often located in high-risk areas. What we’re celebrating here is the popular ingenuity that allows people to survive the many crises as best they can. But this creativity is never enough: the state must also play its part,” he says.

Like all the museum staff, David was born and raised in Ciudad Bolivar. On weekends, he welcomes visitors; during the week, he works as a social worker, organizing tutoring and family planning workshops in public schools. In the evenings, he prepares for a master’s degree in cultural heritage at Lasalle University in downtown Bogotá. Like many of his compañeros, his destiny seems to have been marked by collective mobilization and the municipal investments that followed.

As we walk back to the center of the city, overlooking a sea of spontaneous construction, we realize what the people of Ciudad Bolívar have achieved. For the time being, they have learned to counteract the neoliberal policies of the colonial “written city” (Rama, 1996). But we can’t help but notice that, despite the tourist boom that is currently fueling Colombia’s economy, only a dozen visitors seem to have made the trip to the Museum on this Sunday. Proof, if any were needed, that the negative stereotypes surrounding the neighborhood are still strong and persistent.

About the authors: Clement Roux is a senior researcher, and Christian Petersheim a research manager at ZEF. Eva Youkhana is a Privatdozent at Bonn University and group leader at ZEF.

Photos by Eva Youkhana and Clement Roux