A One Health momentum in the midst of Accra’s rapid urbanization

This blog post was written by Abraham Kidane, Public Health Veterinarian and Jaqueline Hildebrandt, Public Health Scientist. Both researchers belong to the One Health & Urban Transformation Graduate School at ZEF (BIGS-DR batch 2021) and conduct research on One Health issues in Ghana. In this blog post they share their experiences and insights from their trip to Ghana in 2022. Abraham’s research focus is on the application and feasibility of One Health in surveillance and health service delivery, and Jaqueline’s on the climate crisis and its influence on health-care practice.

Akwaaba

The sunrise in Accra appeared to say Akwaaba, the Ghanaian way of warmly saying Welcome. A special welcome for those of us who found ourselves away from the European winter. The sunrise felt like a promise for a good start and a successful work day ahead while the road traffic congestion ensued doubts. The sunrise dimmed by traffic jam and its polluted air were a reminder of ‘One Health and Urban Transformation’. Our project focus ‘One Health’ entails a promise for healthier humans, animals and a healthier environment in the face of conventional practices and growing health risks in a rapidly urbanizing city[1]. One might start to wonder if and how One Health promises could be delivered in the light of rapid urbanization[2] and rising urban health risks. Thus, we are presenting lessons learned through one-on-one stakeholder engagement, workshop, and site visits undertaken by the authors to understand One Health in the urban context of Ghana’s Greater Accra Metropolitan Area. Akwaaba!

What’s One Health?

The One Health commission defines One Health as “a collaborative, multisectoral, and trans-disciplinary approach, working at local, regional, national, and global levels to achieve optimal health (and well-being) outcomes” where the interconnections and interdependency between people, animals, plants, and their shared environment is duly acknowledged[1].

Urbanization and health risks in Ghana

Ghana has seen significant in-migration and a demographic shift. The number of people living in urban areas has increased from 23% in 1960 to 57% in 2020[1] and is estimated to rise up to 72.3% by 2050[2]. Due to development disparities between Ghanaian regions, the expected growth rates widely differ across the country from 25.4% to 91.7%.[3] Despite the widely acclaimed economic gains, urbanization is associated with poor urban governance, planning and development. In cities like Accra, the demographic shift has led to the development and expansion of informal settlements, with an estimated 30% of the country’s population living in slums[4]. Steps taken to address the expansion of slums have involved evictions and demolitions of informal settlements whereas constructive efforts to support the urban poor have been scant.

Ghana’s rich wildlife biodiversity is facing an increasing environmental degradation that results in less natural habitat. Ghana is considered one of the global hotspots for emerging zoonotic diseases[5]. The country is also located at the epicenter of an epidemic-prone African sub-region, with a history of epidemics like Ebola. In recent years, emerging diseases such as Chikungunya or Dengue fever have been reported in the country. Urban health risks due to zoonotic diseases remain imminent in the light of a growing human population, human mobility and a high demand for animal protein. The latter has led to a rising consumption of bush meat, an expansion of intensive animal farming and growing imports of animal products and by-products. Ghana has seen a rise in import of poultry meat from 115,335 tons in 2015 to 283,829 in 2020[6].

The rise in aquaculture and fish farming practice, urban livestock farming and inadequate food-safety practices, added by pet-rearing and selling practices observed during our site-visit can contribute to the rise of health threats such as Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR). Frequent weather events like flooding, also play a part in Accra in the rise of outbreaks of diseases on top of causing destruction to the fragile sewage infrastructure system and economic activities. The daily traffic congestion seen in Accra presents a concern to the air and noise pollution, one of the top environmental stressors. Air pollution is potentially leading to non-communicable diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes and mental health problems, which are among the growing health challenges in the country. Similarly, the high waste generation and landfill-sites we saw in the city have the potential to serve as a breeding ground for rats and dogs, facilitating maintenance and cross-species transmission of diseases like Rabies and Leptospirosis.

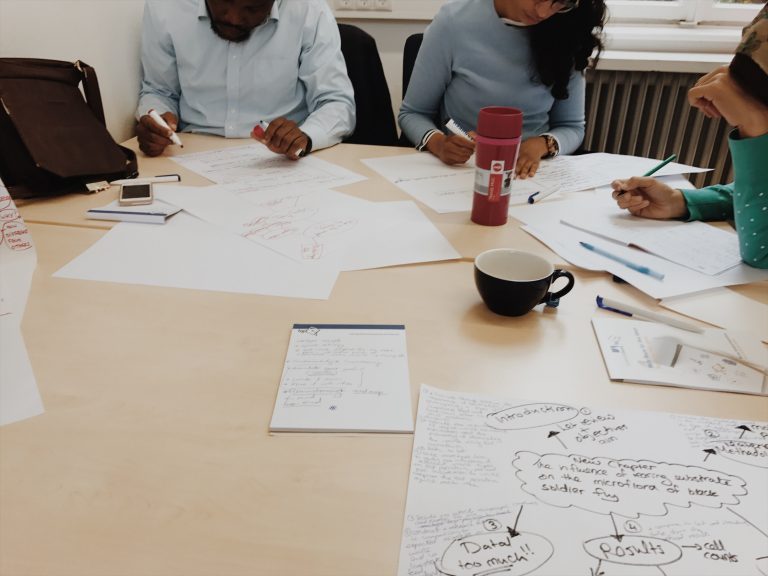

One Health and Urban transformation Workshop in Accra in cooperation with the Institute of Statistics, Social and Economic Research

The One Health and Urban transformation workshop was jointly organized by the Institute of Statistics, Social and Economic Research (ISSER) and the Center for Development Research (ZEF) on February 8, 2022. The aim of the workshop was to facilitate expert consultations and discussions on urban health risks & potential solutions, particularly focusing on Zoonotic Diseases (Surveillance, One Health Education, Operationalization), urban transformation and migrant livelihoods. The workshop was organized to help identify local needs and priorities which could then be aligned with the proposed research topics. The participants represented stakeholders from the human, animal, and environment sectors. The final group was comprised of 30 people of Educational/Research Institutions mainly from Ghana and broader West Africa: different schools of the University of Ghana, Public Agencies, Representatives from the Ghanaian Government, International Donors and Practitioners.

Our constructive open dialogue identified a set of most significant health concerns for metropolitan Accra, which require more attention in the future: extreme heat, non-communicable diseases, and potential zoonotic diseases risk from the growing trend of ownership of wildlife animals as pets, bush meat use, and infestation of rodents within informal settlements.

One Health momentum in the Greater Accra Metropolitan Area

One Health has gained attention in Ghana. Critical steps were taken to operationalize the concept at local and national levels. This was done by forming a One Health technical working group and a national process of joint prioritization of diseases which involved experts from public health, veterinary, and environment sectors. Among other zoonoses, Rabies was identified as a shared priority of the One Health agenda across the three sectors. Joint multi-sectoral dialogues further led to the development of joint strategies on Antimicrobial Resistance, Rabies, and additionally a draft ‘One Health policy’, which is expected to be approved at Ministerial and Parliament levels.

Nonetheless, translation and application of these strategies in the dynamics of urban and mainstreaming the One Health agenda across sectors and existing systems including municipalities is not straightforward. Whether or not the gained One Health momentum could address urban health challenges depends on several factors. On the one hand, it is not clear to what extent the momentum is in full force (i.e. if stakeholders that are relevant at local, sub-national, and national levels in addressing complex urban health, societal, and environmental issues are brought on board). On the other, it is unsure if their contribution is acknowledged.

Furthermore, it is essential how well the ‘One Health policy’ draft is positioned to address societal and environmental challenges, which are central to overcome urban health risks and vulnerabilities. In other words, whether the policy is designed to be proactive rather than reactive. Despite the fact that such a One Health policy is motivated by pandemic threats, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic crisis has shown that a reactive (‘firefighting’) strategy comes at a high cost of human lives, livelihoods, and economies. While the policy support to formal data sharing and reporting among public health, animal health, and environmental health sectors remains useful for early detection and response to outbreaks, the consideration of environmental drivers including infrastructural constraints guarantees sustainability in the long run. In this regard, the role of good urban governance and policy in keeping pace with rapid urbanization and health risks through equitable urban development and engagement of underserved communities is important.

Moreover, the level of commitment among sectors towards resource allocation to existing plans can facilitate or hinder the progress towards a set common goal. In the case of rabies, the investment on mass vaccination of dogs creates herd immunity among dogs and ultimately eliminates human deaths due to rabies – without the need to establish a herd immunity in the human population. The joint prioritization of rabies and the action plan developed by involving veterinary and public health sectors, however, did not yet materialize in practice and remains stalled, lacking financial backing. In this regard, the presence of aligned and synergic policies which include resource mobilization and budget allocation from sectors involved can serve as the litmus test for viability of the One Health collaboration and if the One Health promise can be delivered against the rising urban health risks. While the question whether the One Health momentum could catch up with rapid urbanization and evolving health risks in Ghana will continue to be an open question and left for us and future researches to answer, there should be precedents towards One Health initiatives: to make a shift from hit-and-run tactics to ‘nature-based solutions’[1] to guide the speed and direction of the One Health momentum to the right direction, securing resilience and sustainability[2].

[1] Schröter, B. et al. Beyond Demonstrators—tackling fundamental problems in amplifying nature-based solutions for the post-COVID-19 world. npj Urban Sustain 2, 4 (2022).

[2] de Leeuw, E. (2020). One Health(y) Cities. Cities & Health, 1–6.

[1] World Bank (2021). Urban population (% of total population) – Ghana. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS?locations=GH (Accessed: September 12, 2021)

[2] UN Habitat (2016), Addressing Rapid Urbanization Challenges in the Greater Accra Region.

[3] Ghana Statistics Service (2021). Ghana 2021 population and housing census. General report volume 3A. Population of regions and districts.

[4] World Bank (2021). Population living in slums (% of urban population) – Ghana. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.POP.SLUM.UR.ZS?locations=GH (Accessed: September 12, 2021)

[5] Allen et al. 2017. Global hotspots and correlates of emerging zoonotic diseases. Nature Communications, 8(1).

[6] FAO STAT (2022). Crops and livestock products. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/TCL (Accessed: March 7, 2022)

[1] One Health Commission (2022), What is One Health? Available at: https://www.onehealthcommission.org/en/why_one_health/what_is_one_health/ (Accessed: June 21, 2022).

[1] UN Habitat (2016), Addressing Rapid Urbanization Challenges in the Greater Accra Region.

[2] Ghana Statistics Service (2021). Ghana 2021 population and housing census. General report volume 3A. Population of regions and districts.