Biodiversity and Gender: how their bonds were strengthened in the UN Convention on Biodiversity

This blog post was written by ZEF senior research Isimemen Osemwegie*, who attended the Global Biodiversity Summit in Montreal in December 2022. Osemwegie is an expert on climate change and biodiversity and a member of the UNCBD Women Caucus.

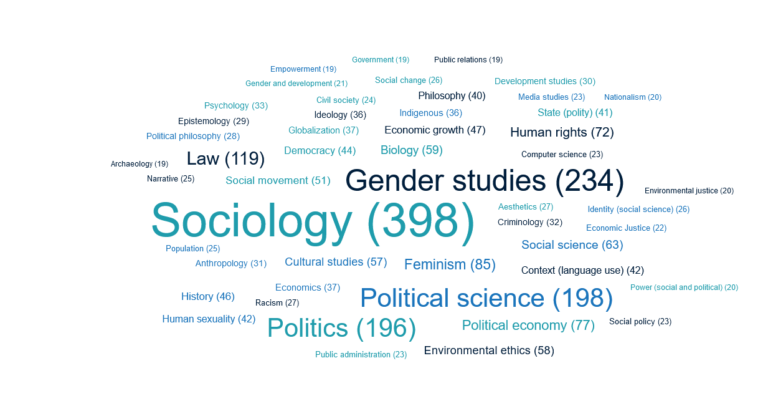

Montreal, Canada’s second-most populous city, welcomed parties and different stakeholders from all over the world to its Palais de Congress between December 7-19, 2022 for a series of international and UN-related meetings on Biodiversity: The 15th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (Part II, COP 15); the 10th meeting of the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety (COP-MOP 10, Cartagena Protocol); and the Fourth meeting of the Conference of the Parties serving as the meeting of the Parties to the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit-sharing (COP-MOP 4, Nagoya Protocol).

The two-week event adopted a comprehensive consultative process, and hosted various plenary sessions, contact group meetings, friends of the chair sections, high-level segments, and over 200 on-site and off-site parallel side events. The overall goal of the side events was to showcase national and organizational efforts on biodiversity conservation, proffer suggestions and recommendations to inform, appeal to, and influence the ongoing legal texts negotiations. From the numerous decision-related documents[1], I will focus on the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework (Post-2020 GBF)[2], but more specifically on its gender-responsive implementation targets.

The Kunming-Montreal post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework

During its 14th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (COP14) in Sharm El Sheikh in November 2018, the process to develop the new global biodiversity Framework (decision 14/34[3]) was adopted. The mission of the new global framework as stated in the first draft[4] released in July 2021, is: “To take urgent action across society to conserve and sustainably use biodiversity and ensure the fair and equitable sharing of benefits from the use of genetics resources, to put biodiversity on a path to recovery by 2030 for the benefit of planet and people“. As a result, the Global Biodiversity Framework is a step toward the 2050 Vision of “Living in Harmony with Nature,” which was adopted by parties in 2010, and a critical contribution to achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. The first draft of the post-2020 GBF included four goals and 21 action-oriented targets related to biodiversity threats (targets 1 – 8), meeting people’s needs through sustainable use and benefit sharing (targets 9 – 13), and tools and solutions for implementation and mainstreaming (targets 14 – 21). However, there was no explicit target mentioning gender-responsive implementation. For more information on the Global Biodiversity Framework text negotiation and modifications, including the virtual part I of the 15th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity in Kunming, China (COP15, October 11 – 24, 2022) and details of the different open-ended working group meetings leading up to the COP 15-part II, visit: https://www.cbd.int/conferences/post2020.

Following several negotiations and modifications, four goals and 23 action-oriented targets were adopted by its 196 member parties in the final text of the Kunming-Montreal post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework adopted in December 2022. Two of these; the targets 22 and 23, are touching on social inclusivity, gender equality, women empowerment and an equitable and gender-responsive implementation.

A piece of history

The UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which has been in force since 1993 became the first multilateral environmental agreement to have a Gender Plan of Actions (adopted as Decision XII/7 at COP 12)[5], adopted in 2008, at its 12th Conference of Parties in Pyeongchang, Republic of Korea. With this, the CBD recognizes the importance of gender considerations in achieving its 2011 – 2020 strategic biodiversity plan, the Aichi Biodiversity targets 67 which had 20 targets organized under 5 strategic goals. Notwithstanding, the only Aichi Biodiversity target mentioning women was target 14, which states that “By 2020, ecosystems that provide essential services, including services related to water, and contribute to health, livelihoods and well-being, are restored and safeguarded, taking into account the needs of women, indigenous and local communities, and the poor and vulnerable”. Despite this, as with the other Aichi targets, target 14 only achieved a 15% implementation success rate[6] among its 196 parties.

Following this shortfall in the Aichi target implementation, during the external review process (23 August – 3 September 2021) of the first draft of the post-2020 GBF, the UN-CBD Women Caucus, led by Ms. Mrinalini Rai, rose to the occasion, took it up a notch, and pushed for a stand-alone gender target (formerly, target 22[7] in earlier versions, now target 23 in the final post-2020 GBF).

The initial proposed text of target 22 reads: “Ensure women and girls equitable access and benefits from conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity, as well as their informed and effective participation at all levels of policy and decision-making related to biodiversity”. Arguing that unlike in the preceding Aichi targets, a stand-alone gender target will advance gender mainstreaming and women empowerment, ensure alignment with the CBD Gender Plan of Actions and build complementarity with the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)[8], particularly SDG 5 (gender equality). The UNCBD women caucus succeeded through lobbying, tact, diplomacy, awareness-raising on social media channels, in birthing a gender-responsive implementation target.

The adoption of the target 23 wasn’t a smooth sail: “gender-responsive” or “gender-sensitive”, what does it matter?

“All areas of human activities have a gender dimension, hence the need for a gender lens in budgeting related to national climate and biodiversity actions”

UN Secretary General António Guterres

Following some modifications, the stand-alone gender implementation target at the start of the Part II of COP 15 negotiations in Montreal, in the non-paper draft version (WG2020-5-CG-4[9]), reads:

“Ensure gender equality in the implementation of the framework through a gender [responsive] approach where all women and girls have equal opportunity and capacity to contribute to the three objectives of the Convention, including by recognizing their equal rights and access to land and natural resources and their full, equitable, meaningful and informed participation and leadership at all levels of action, engagement, policy and decision-making related to biodiversity.”

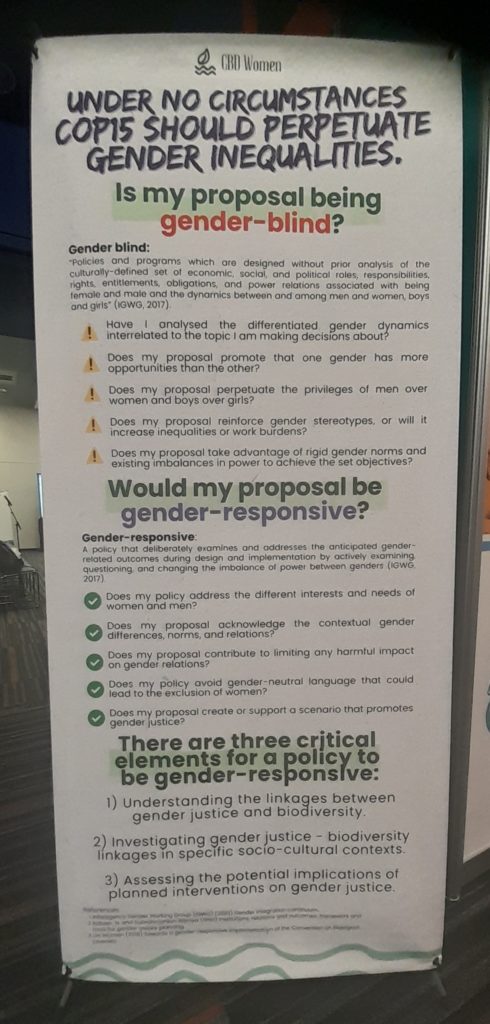

However, this target was met with a rebuttal at the December 6th plenary session, following objections by a party to the inclusion of the word ‘responsive’ in the text of the target. As negotiations stalled, ‘responsive’ was relegated to a bracket, and target 23 headed for another round of negotiations. ‘Sensitive’ was one of the alternative texts proposed to replace ‘responsive’. Following this development, the UNCBD Women Caucus set up an on-site display to provide a detailed explanation of ‘gender-responsiveness’, amplified voices through side events and social media channels, and garnered support from more parties as to why ‘gender-sensitive’, an inertia term clearly lacking in force of compliance, is not acceptable.

Furthermore, as part of the advocacy campaign, in her opening statement on Dec. 7[10], the UN CBD women reminded parties of the adoption of ‘gender-responsive’, as one of the thirteen principles guiding the preparatory process for the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework at the UN CBD COP14 in Sharm-El-Sheikh, Egypt, 17-29 in November 2018 (under CBD/DEC/COP/14/34 Annex Para 2.A.c[11]). As a result, replacing the term ‘gender-responsive’ was non-negotiable in order to ensure a comprehensive and participatory, that is, whole-of-society implementation process.

Gender-sensitive refers to acknowledging gender needs and vulnerabilities without addressing the root causes that contribute to gender inequality, whereas gender-responsive goes a step further and strives for equality and better development outcomes by acknowledging gender dynamics and taking actions that respond to the specific needs of women, men, boys and girls.

What next? Need for capacity building

“As integrated within its goal D, target 23 and captured in the newly adopted gender plan of action (CBD/COP/15/L24[13]), there is need to develop and/or strengthen the capacities of parties and relevant stakeholders for a shared vision and common understanding of how to weave the gender-related targets into the fabrics of national biodiversity actions, the efficient coordination of resources and associated financial mechanisms to achieve the intended objectives of the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework”.

Isimemen Osemwegie

After this historic victory at COP 15 in Montreal, the work is far from done. Adoption of these gender-related targets (targets 22 and 23) establishes gender-responsive Global Biodiversity Framework implementation as a shared interest and creates a global cohesive picture of desired outcomes. These goals, however, should not be denied the human and institutional resources needed to coordinate collective actions and move them forward. As a result, the question of how these targets translate into biodiversity actions, that is, actions to mitigate ongoing biodiversity loss, arises. Although indicators[12] have been established as measures of target achievement, capacity development on ‘Gender and biodiversity’ is the pivot of an effective gender-responsive Global Biodiversity Framework implementation. Finally, how this bond between gender and biodiversity will play out in the national contexts, relies majorly on credible commitments and actions.

*Dr. Isimemen Osemwegie is the Assistant Coordinator of the Capacity Development for Biodiversity Experts in West, Central and East Africa – CABES , funded by the International Climate Initiative (IKI) of the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection (BMUV). She is also a member of the UN CBD Women Caucus.

[1] See https://www.cbd.int/conferences/2021-2022/cop-15/documents

[2] See 221222-CBD-PressRelease-COP15-Final.pdf

[3] See 14/34. Comprehensive and participatory process for the preparation of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework (cbd.int)

[4] See First draft of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework (cbd.int)

[5] See https://www.cbd.int/decision/cop/?id=13370

[6] See https://www.cbd.int/aichi-targets/target/14

[7] See https://www.women4biodiversity.org/target-22-gender-in-post-2020-global-biodiversity-framework/

[8] Watch https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZYp7XM1uRdI

[9] See RECOMMENDATION ADOPTED BY THE WORKING GROUP ON THE POST-2020 GLOBAL BIODIVERSITY FRAMEWORK (cbd.int)

[10] See https://www.cbd-alliance.org/index.php/en/2022/opening-statements-cop15

[11] See 14/34. Comprehensive and participatory process for the preparation of the post-2020 global biodiversity framework (cbd.int)

[12] See Mechanisms for planning, monitoring, reporting and review (cbd.int)

[13] See Gender Plan of Action (cbd.int)