Following the science at COP26: Insights and Observations on the Integration of Scientific Findings in International Climate Policy

This blog post was written by Sara Velander and Niklas Wagner, both doctoral researchers at ZEF’s doctoral program BIGS-DR. They spent nearly two weeks at the COP26 in Glasgow, UK (Oct. 31- Nov. 12, 2021) and observed six negotiations sessions, attended 14 side events, and conducted 19 semi-structured interviews there. Read about their impressions, observations and conclusions!

Climate Change and the Science-Policy Divide

As early as in 1859, the Irish scientist John Tyndall was able to show that carbon dioxide in the atmosphere would drastically change the earth’s climate. With these findings, he provided the foundation for a broad body of scientific literature on anthropogenic climate change pointing out the dangers of greenhouse gas emissions for humans and biodiversity.

These warnings made by scientists, however, have been massively ignored over the past centuries by political decision-makers worldwide: Greenhouse gas emissions have been reaching unprecedented levels year after year. And we can observe the catastrophic consequences of this development as clearly as never before. Thousands of people on the globe have been suffering, dying or losing the basis of their livelihoods because of the effects of rising sea levels and extreme weather events like droughts and floods. In addition, biodiversity extinction rates are skyrocketing.

In light of this science-policy divide when it comes to solving complex and multifaceted problems such as climate change,

we as researchers have been asking ourselves: How do we bridge this gap between science and policy?

Effective Science Policy Interfaces could be pivotal for this. These are platforms connecting policymakers and scientists through the exchange of knowledge on societal issues. One of the most prominent Science Policy Interfaces is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a United Nations body that systematically assesses and synthesizes scientific findings on climate change and communicates it to policymakers through a series of assessments and special reports.

Research objectives on the IPCC and other Science Policy Interfaces at COP26

The IPCC has been playing a crucial role in the development of international climate governance since the 1990s. One of the major players in the international climate governance system is the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which entered into force in 1994 and has been holding its Conference of the Parties (COP) on an annual basis since then. The COPs have turned into huge Global Climate Summits with thousands of participants from all over the world. This year’s COP 26 was held in Glasgow, United Kingdom, from October 31 – November 12.

Given the historical inter-linkages and the role that IPCC has been playing in the development of other Science Policy Interfaces over the past few decades, we decided to conduct research at the COP26. As it is at these conferences where decision makers shape landmark policies on the mitigation and adaptation to climate change with sweeping impacts across the world. The IPCC is having a notable presence in these conferences through its role of informing policymakers about the latest findings on climate change.

Thus, we considered COP26 in Glasgow as an ideal site to collect data for our doctoral research examining the legitimacy and complexity of Science Policy Interfaces like the IPCC.

Attending the conference and talking to different stakeholders there would also help us understand how policy makers and scientists view the IPCC as an institution and what impact its reports have on international climate policy making.

We were grateful to receive accreditation for both weeks of the conference as members of the University of Bonn, which is officially an observing organization of the UNFCCC. In the weeks leading up to the COP, we spent several hours with our supervisors preparing a comprehensive interview guide for the semi-structured interviews we had planned to hold with IPCC scientists and negotiators. In addition, we tracked relevant events and negotiation items for participant observation and reached out to established contacts in our network. As we departed to Glasgow by train on October 30, equipped with the necessary research materials (informed consent forms, one-page research briefs, and business cards) and a detailed game plan, we considered ourselves quite prepared for one of the biggest UN climate conferences in history.

However, once we arrived and after we retrieved our badges the next day, there was a crude reality check on the rollercoaster-whirlwind-craziness this lengthy, high-level conference would bring to our lives. Moreover, we had to rapidly familiarize ourselves with in-person exchanges after handling mostly remote and online human interactions only over the past 18 months, as a result from Covid-19 pandemic restrictions.

Insights from research activities

The first two days at the COP we basically spent orienting ourselves at the spacious conference venue, testing the interview guide and interview durations, checking the latest updates on the schedule for events related to the IPCC, and already reaching out to some preliminary contacts with negotiators. One of the places we explored was the Pavilions area, which was, essentially, a large warehouse-like space made up of a labyrinth of diverse, decorated, colorful rooms representing different countries and organizations.

While roaming the pavilions, we discovered the Science Pavilion, a medium-sized room with a small stage and seating for around 25 people (quite small in comparison to some pavilions). The pavilion was co-hosted by the IPCC, the UK Meteorological Office, and the World Meteorological Organization. We were elated realizing how useful this space would be for our research as we spoke to some of the IPCC staff about our research ideas and perused the many IPCC-related events they were hosting throughout the two weeks. It felt like it was another conference in itself. At that point we knew that we would spend most of our time at COP26 in this pavilion.

In the first week, we also attended a UNFCCC process closely related to our research called the Structured Expert Dialogue. The process was established in 2012 to facilitate discussions between parties and experts on scientific knowledge for evidence-based climate policy formulation. At COP26, the two-day second meeting of the structured expert dialogue of the second periodic review[1] took place in the first week of the conference, in parallel with the negotiations of the Subsidiary Body for Scientific and Technological Advice (SBSTA). The first day we saw presentations from the IPCC on the newly published Working Group 1 contributions to the Sixth assessment report (AR6), focusing on the physical science basis of climate change.

There was significant coverage throughout COP26 on this report as we frequently saw the Working Group 1 co-chairs present the findings at many different events. There were also presentations from other reports, including the United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) Emissions Gap Report and the Fourth Biennial Assessment and Overview of Climate Finance Flows.

The key messages of these reports were that “changes in the climate are rapid, widespread and intensifying and that humans are the main cause”

with the average global surface temperature reaching 1.1 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels due to high carbon dioxide emissions resulting from burning fossil fuels and deforestation. You can hear more about the latest AR6 findings in this video.

For the second day of the dialogue, there was a regional focus with the WMO Regional Climate Centres and the IPCC presenting findings on climate change specified for each global region. During both days, the presentations were followed by a riveting exchange between parties attending the dialogue and experts presenting the findings. Some parties were voicing their concerns about the severity of the latest findings on climate change, the implications this will have on society, data gaps in the Global South (Africa in particular), as well as cross-scalar outreach strategy and education of the scientific findings.

We had a similar impression of other events and negotiations taking place that first week, including a special event hosted by the IPCC and SBSTA. It took place in the large plenary hall and parties had the opportunity to hear about the findings of AR6 and make comments, pose questions, and share their views on what the latest science is saying on the state of the earth’s climate. Parties’ concerns were a further issue of reflection in the negotiations of one of the SBSTA agenda items on systematic observation and research. Here, we observed a continuation of the discussions on the reports that the IPCC, WMO and UNEP presented in the structured expert dialogue.

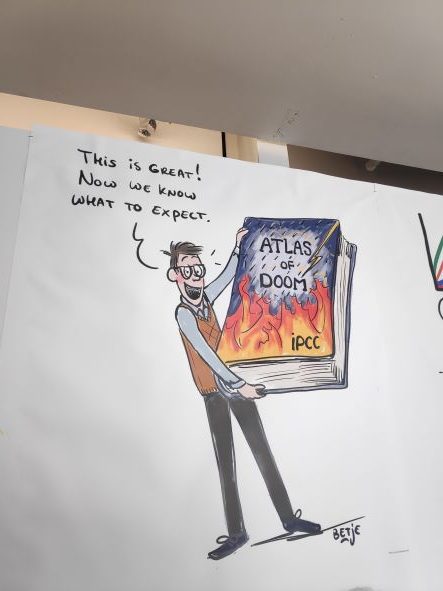

Discussing the sixth Assessment Report …

In sum, our first week was full of participant observation and networking as we found ourselves running between negotiation halls, the science pavilion, and side-event rooms to ensure we were able to attend all the research-related events. It was primarily in the second week where we found ourselves conducting most of our interviews as many of the negotiators and IPCC authors we met were only available after the SBSTA negotiations, which were closing by the end of the first week.

In total, we observed six negotiations sessions, attended 14 side events, and conducted 19 semi-structured interviews, with more online interviews scheduled for contacts who would be available only after the conference.

When reflecting on our observations, experiences and conversations, we have found a high trust in the IPCC and science among negotiators at COP26. Many of them were claiming that they think the IPCC provides the best available knowledge on climate change. On the other hand, we also found low awareness of the content of the reports among several negotiators, unless they were directly involved in the IPCC process as focal points or contributing authors or were following science-related agenda items in the SBSTA negotiations. The negotiators and a few of the IPCC authors we spoke to also noted the underrepresentation of knowledge from women, the Global South and indigenous, local communities in the scientific reports.

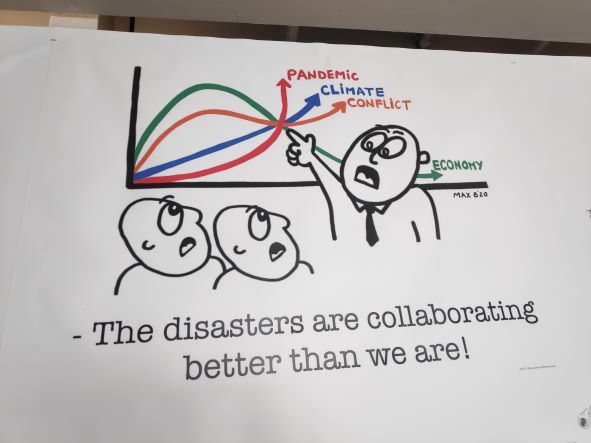

Concerning complexity, many negotiators were unaware of other science-policy interfaces, particularly from different sectors.

Yet, almost all the IPCC scientists and negotiators agreed that more collaboration is needed between organizations creating reports on climate change.

Above all, among all stakeholders we spoke to and heard from there was consensus on the importance of science in guiding policymaking on the issue of climate change and the need for coherency between agreements made at COP26 and the latest scientific findings.

Role of Science in the Political Outcomes of COP26

Our findings indicate that science and the IPCC are considered important in the context of a COP, even if they are not the decisive voices in the decision-making processes. But we also discovered much ‘silo thinking’ concerning the multifaceted problems we are facing.

These findings are also mirrored in the political outcomes of this year’s COP, the Glasgow Climate Pact. This document highlights in the very first chapter under the title “Science and urgency” the importance of science and the other Science Policy Interfaces.

It not only “Recognizes the importance of the best available science for effective climate action and policymaking” and “welcomes the contribution of Working Group I to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Sixth Assessment Report and the recent global and regional reports on the state of the climate from the World Meteorological Organization”, but also “stresses the urgency of enhancing ambition and action in relation to mitigation, adaptation and finance in this critical decade to address the gaps in the implementation of the goals of the Paris Agreement”.

This urgency, however, is not reflected in the actual outcomes: Market mechanisms under Article 6 allow for old carbon credits from the Kyoto Protocol Period, threatening environmental integrity. Moreover, the goal for financing mechanisms to facilitate long-term adaptation has not been reached, and India and China have watered down the ‘phase-out’ of coal to a ‘phase down’. To quote one of our interviewees: “Policy is often not about evidence but rather about values and interests”.

Let’s hope that interests and values of politicians, though, will be more closely aligned with what science says is necessary in the future.

About the authors: Niklas Wagner is also part of the One Health and Urban Transformation Graduate School and Sara Velander of the project At the Science Policy Interface: LANd Use SYNergies and CONflicts within the framework of the 2030 Agenda (LANUSYNCON).

[1] In COP25 in Madrid, parties agreed to conduct a second periodic review on the adequacy and progress towards achieving the long term goal “to hold the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels.” https://unfccc.int/topics/science/workstreams/periodic-review#eq-2