Edible Insects & the future of food security: My experience as a lecturer in the Philippines

“Travel isn’t always pretty. It isn’t always comfortable. Sometimes it hurts, it even breaks your heart. But that’s okay. The journey changes you; it should change you. It leaves marks on your memory, on your consciousness, on your heart, and on your body. You take something with you. Hopefully, you leave something good behind.” – Anthony Bourdain

They asked me..I said YES… to the Philippines ツ

I received an invitation from SEARCA i.e. the Southeast Asian Regional Center for Graduate Study and Research in Agriculture to deliver a module on edible insects at a summer school in the Philippine. SEARCA was founded in 1966 and is one of the oldest among 24 specialist institutions of the Southeast Asian Ministers of Education Organization. Since then, SEARCA has been working to strengthen institutional capacities in agricultural and rural development in Southeast Asia.

The module on edible insects was part of Food Security Center (FSC) 2019 Summer School entitled “Transformative Changes in Agriculture and Food Systems”. More information on the in total three summer school modules organized by the Food Security Center of the University of Hohenheim, Germany, can be found here: https://fsc.uni-hohenheim.de/en/searca_fsc_summer_school

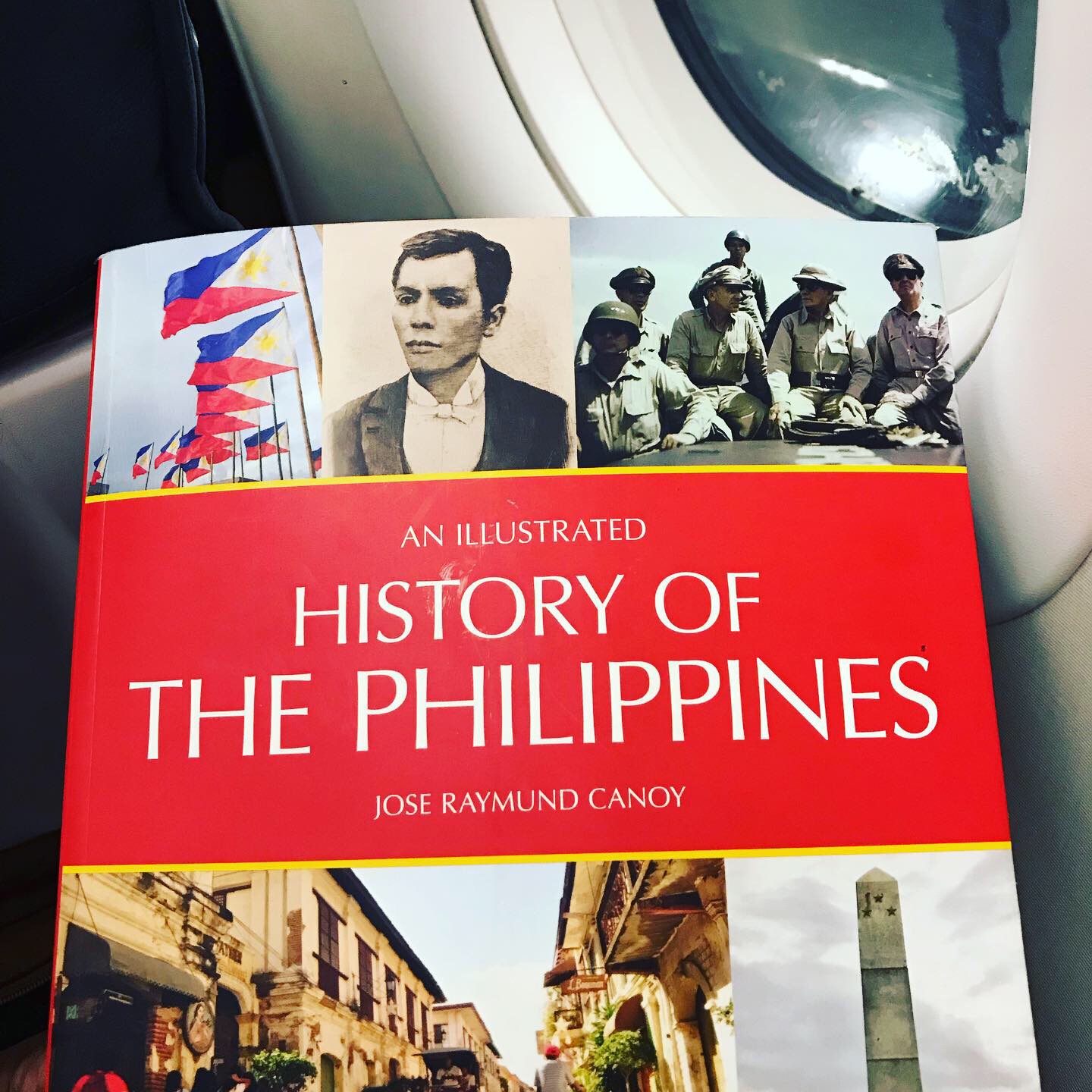

I didn’t feel bored despite the very long flight from Germany to the Philippines as I was reading an interesting book on board. I love history & culture books and the book “An Illustrated History of the Philippines” by Jose Raymund Canoy with its color images, maps and a detailed timeline is quite a compelling read — perhaps enough to get even those disinterested in history hooked. I highly recommend this book to anyone planning a trip to the Philippines. For a detailed book review please refer to the following link: https://cnnphilippines.com/life/culture/2019/03/04/Jose-Raymund-Canoy-interview.html

Safe and Sound.. Manila-bound

On the first day of my module I attended a talk on “ICTs in Agriculture and Agribusiness: Past Development, Current Status, Perspectives, and Development Needs” which was given by Prof. Reiner Doluschitz, Director of the Food Security Center (FSC) in Hohenheim, Germany. The talk was part of the “Agriculture and Development Series Seminar” organized by the Knowledge Management Department of SEARCA.

After the seminar, I invited the students to watch a documentary on entomology in South East Asia and following the screening, they had the opportunity to enjoy some insect snacks that I carried along with me from Germany, thanks to my friend Folke Dammann and his start-up Snack-Insects.

During the one-week long “Edible Insects” module, I explored with the students insects as alternative sources of subsistence and protein. I shared with them research results indicating their nutritional benefits. I talked to them about the reasons why we should ditch beef burgers and eat insects instead. For instance, the favor we would be doing to our already depleted lands and natural resources and the reduced levels of green house gases that we would produce. We also had a view on entomophagy’s history and culture vs. the Western perception towards insects consumption. I also introduced them to insect for food and feed production systems. As a closing activity, the students divided in teams and developed their own business pitch to promote edible insects.

A guided tour through the campus of the University of the Philippines Los Baños

The University of the Philippines Los Baños (UPLB) was originally established as the University of the Philippines College of Agriculture (UPCA) in 1909. Edwin Copeland, an American botanist and Thomasite from the Philippines Normal College in Manila served as its first dean. Classes first began in June 1909 with five professors and 12 students initially enrolled in the program.

The 1,098 ha (2,710-acre) Los Baños campus houses UPLB’s academic facilities, as well as experimental farms for agriculture and biotechnology research. I was lucky to visit most of the prominent buildings of the Los Baños campus including the Dioscoro L. Umali Hall, Main Library and the Student Union which were all designed by the National Artist/Architect Leandro Locsin. I also visited the iconic Oblation, Alumni Plaza, Freedom Park and Baker Memorial Hall. In addition, I had a quick look at the Mt. Makiling Botanic Garden which is home to diverse flora and fauna, and has more tree species than the continental United States.

Observing the sunset at IRRI : Home of the controversial “Golden Rice”

The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) is an international agricultural research and training organization and one out of 15 centers of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). IRRI has its headquarters in Los Baños, Laguna in the Philippines and offices in seventeen countries with ~1,300 staff. IRRI is well-known for its contribution to the “Green Revolution” movement in Asia during the late 1960s and 1970s, which involved the breeding of “semi-dwarf” varieties of rice that were less likely to lodge (fall over). IRRI’s semi-dwarf varieties, including the famous IR8, saved India from famine in the 1960s.The varieties developed at IRRI, known as IR varieties, are well accepted in many Asian countries. In 2005, it was estimated that 60% of the world’s rice area was planted to IRRI-bred rice varieties or their progenies.

Enjoying the tropical tastes of the Philippine

A day trip to Manila : “Pearl of the Orient”

Manila began as a small tribal settlement on the banks of the Pasig River near the mouth of Manila Bay. It took its name from a white-flowered mangrove plant – the nilad – which grew in abundance in the area. Maynilad, or where the nilad grows, was a fairly prosperous Islamic community ruled by Rajah Sulayman, descendant of a royal Malay family.

As one of the oldest settlements in the Philippines—an important node in the Spanish galleon trade for centuries, and a former American colony in the Pacific—Manila boasts plenty of history and culture in its streets that not even the bombs of World War II could wipe out.

For hundreds of years, the walled city of Intramuros was Manila: the nerve center of the Spanish occupation in the Philippines, home to several thousand Spanish colonists, their families, and their Filipino servants.

The moment I entered the walled city of Intramuros, I felt like a time machine has brought me back to the Spanish colonial period in the Philippines. Going around this oldest district in Manila, I fell in love with its old-world charm.

Intramuros was erected on the ruins of a Malay settlement at the mouth of the Pasig River. Its strategic location attracted the attention of the Spanish conquistador Miguel Lopez de Legazpi, who took over the area in 1571 and proclaimed it as the Philippines’ colony’s new capital.

From when the city was built in 1571 until the end of the Spanish rule in 1898, Intramuros was Manila. The name Intramuros means “inside the wall.” For more than 300 years, Intramuros served as the center of the Spanish occupation, originally built to be the residence of Spanish government officials and their families. It was where the most influential and wealthy citizens of colonial Manila lived. The natives and Chinese were not allowed to live inside Intramuros, only the Spanish elite and mestizos.

The walls of Intramuros were meant to protect the city from foreign invasions. The walls were six meters high and three kilometers in length, covering an area of about 160 acres. Entry and exit were only through its seven fortified gates. Within the vast walls, throughout the 51 blocks of the city, were churches, hospitals, government offices, military barracks, schools, and houses of the Spanish elite.

For over 300 years, Intramuros was the center of Spanish political, religious, and military power in the region. The walled city has been devastated by battles, fires, and earthquakes but has survived the test of time. It holds bittersweet memories of the colonial past, a heritage worth preserving and sharing with the world. Today, Intramuros is a prominent tourist spot where visitors can experience Spanish-era Manila through the walled city’s churches, restaurants, and museums.

I walked the cobblestone streets with lamp posts from 1800s, saw old Spanish houses, gardens, and churches. I also noticed that security personnel were dressed like Spanish-era civil guards or Guardia Civil. If you ever plan a visit to Intramuros , do some research and wear comfortable shoes. Don’t forget to capture the charm with your camera and bring a bottle of water along.

Fort Santiago was built by Spanish conquistadors in 1571, replacing the destroyed fortress belonging to the last datu (king) of pre-Hispanic Manila.

Over the years, Fort Santiago served as a fortress against marauding Chinese pirates, a prison for Spanish-era political prisoners, and a Japanese torture chamber in World War II. American bombs deployed during the Battle for Manila almost succeeded in destroying the Fort altogether. A postwar government initiative helped restore Fort Santiago and clean its bad Juju away. Today, Fort Santiago is a relaxing place to visit and an enlightening portal into the Philippines’ colonial past. It contains a peaceful park, battlements overlooking the Pasig River, and a memorial museum to the Philippines’ national hero Jose Rizal.

Remembering a Filipino National Hero: Rizal Shrine

“How long have you been away from the country?” Laruja asked Ibarra.

“Almost seven years.”

“Then you have probably forgotten all about it.”

“Quite the contrary. Even if my country does seem to have forgotten me, I have always thought about it.”

― José Rizal, Noli Me Tángere

José Rizal (born June 19, 1861, Calamba, Philippines—died December 30, 1896, Manila), patriot, physician, and man of letters who was an inspiration to the Philippine nationalist movement.

The son of a prosperous landowner, Rizal was educated in Manila and at the University of Madrid. A brilliant medical student, he soon committed himself to the reform of Spanish rule in his home country, though he never advocated the Philippines’ independence. Most of his writing was done in Europe, where he resided between 1882 and 1892. In 1887 Rizal published his first novel, Noli me tangere (The Social Cancer), a passionate exposure of the evils of Spanish rule in the Philippines. A sequel, El filibusterismo (1891; The Reign of Greed), established his reputation as the leading spokesman of the Philippine reform movement. He published an annotated edition (1890; reprinted 1958) of Antonio Morga’s Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas, hoping to show that the native people of the Philippines had a long history before the Spaniards invaded the country. He became the leader of the Propaganda Movement, contributing numerous articles to its newspaper, La Solidaridad, published in Barcelona. Rizal’s political program included integration of the Philippines as a province of Spain, representation in the Cortes (the Spanish parliament), the replacement of Spanish friars by Filipino priests, freedom of assembly and expression, and equality of Filipinos and Spaniards before the law. After having spent 10 years in Europe, Rizal returned to the Philippines in 1892. He founded a non-violent-reform society, the Liga Filipina, in Manila, and was deported to Dapitan, on Mindanao, the second largets island of the Philippines. He remained in exile for the next four years. In 1896 the Katipunan, a Filipino nationalist secret society, revolted against Spain. Although he had no connections with that organization and he had had no part in the insurrection, Rizal was arrested and tried for sedition by the military. Found guilty, he was publicly executed by a firing squad in Manila. His martyrdom convinced Filipinos that there was no alternative to independence from Spain. On the eve of his execution, while confined in Fort Santiago, Rizal wrote “Último adiós” (“Last Farewell”), a masterpiece of 19th-century Spanish verse.

I die without seeing dawn’s light shining on my country… You, who will see it, welcome it for me…don’t forget those who fell during the nighttime.

― Jose Rizal

During the last days of his life, from November 3 to December 29, 1896, Jose Rizal was held in the Fort Santiago barracks on the western side of Plaza de Armas, where he was sentenced to death for supporting a brewing revolution against Spanish rule. From Fort Santiago, Rizal was marched out through Postigo Gate to Bagumbayan field (the site of today’s Rizal Park) and executed by a firing squad on December 30, 1896. Rizal’s route as a dead man walking has been preserved as a series of bronze footprints leading out from Fort Santiago to the gate exiting Intramuros. The origin of the footprints—part of the old barrack—has been spruced up and transformed into the Rizal Shrine, where Rizal’s life unfolds before the visitor. Starting with a timeline of Rizal’s life, the exhibit guides guests through numerous rooms depicting his martyrdom (complete with the only part of Rizal’s anatomy viewable by the public, his bullet-shattered vertebra); a replica of the courtroom that decided his fate; and a room that features Rizal’s legacy—from reproductions of his sketches and sculptures to his last poem engraved in marble and taking up an entire wall.

I would like to extremely thank Dr. Maria Cristeta N. Cuaresma, the Program Head and Ms Blessie P. Saez, the Program Support Staff of the Graduate Education and Institutional Development at SEARCA for their support and help even before my arrival to the Philippines. I am also thankful to Ms Lorielle Angelei V. Malveda and the rest of SEARCA’s support staff as well as Mama Irma, Mai Mai and the rest of the very kind and helpful staff at the SEARCA guesthouse.

Last but not least, my gratitude to the Food Security Center (FSC) at the University of Hohenheim and the German Agency for Academic Exchange (DAAD) for sponsoring my trip to the Philippines.

Marwa’s visit to the spa was in line with her preparations to an exciting journey that she waiting…

Marwa’s visit to the spa was in line with her preparations to an exciting journey that she waiting…