Postcard from Paris/ Rive Gauche: Urban renewal and controversies about the Right to the City in the South

The quarter Rive Gauche (literally: left bank) between the Seine River and the Avenue de France has undergone urban renewal since 1995. One of the objective was to create better connections between the city and the river by extending the main roads to the banks, as well as by building waterfront promenades and rehabilitate old docks. It was by pure chance that I came to a conference venue in a quarter where waterfront development was going on.

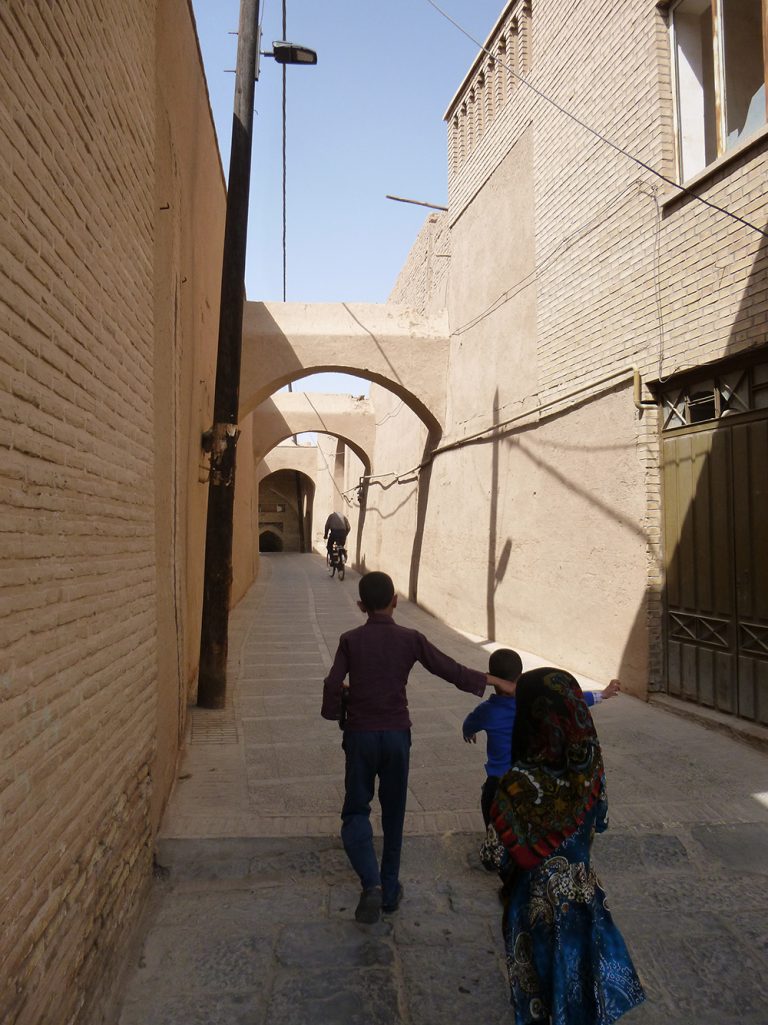

Masséna-Nord – Grand Moulin with the campuses of the University Paris Diderot and the École Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture Paris-Val de Seine, is located where the so-called Boulevard Péripherique, the large ring road, divides the 13th arrondissement from Paris´s suburbs. The quarter by the river has mainly been used by industries and served as residential area for their workers. Where the Avenue de France ends, in the South, the urban landscape immediately turns into an industrial landscape with railway tracks, warehouses, a power station and factories.

[aesop_image imgwidth=”100%” img=”https://blog.zef.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Paris_Irit_Eguavoen_26.jpg” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

[aesop_image imgwidth=”100%” img=”https://blog.zef.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Paris_Irit_Eguavoen_3.jpg” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Figures: Two contrasting urban landscapes meet at the Boulevard Masséna

The wide canyon of railway tracks that had cut off areas near the Seine from the eastern parts of Rive Gauche is currently superstructed with new high rising offices and modern residential buildings. The superstructure will reconnect different parts of the city. Additional space for construction and public spaces is provided. The Avenue de France has been turned into a chic, modern boulevard with comfortable pedestrians, and two safe lanes for bicycles on a traffic island going all along the avenue in the middle of the road. Power terminals for shared electric cars, shared bikes and bicycles, as well as hybrid engine busses, the metro and trams to encourage the use of public transport and help students to get to campus.

Everything looks so renewed in Masséna-Nord that I immediately asked myself: what has been at this place before and why was it so radically removed? And who had to leave to make place for students, business people and the current residents? Apart from some old industrial buildings that the university had converted into lecture halls, not many old houses seem to have survived the renewal. I had not much time to walk around and find the answer. And after our conference sessions, it was always too dark to stroll along the river side. So I will need to do some reading and come back one day… But Rive Gauche was certainly an interesting location for a conference where the Right to the City in the South was discussed.

[aesop_gallery id=”2410″ revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Figures: Our venues make reference to their industrial past: Olympe de Gouges from outside and the Halles aux Farine from inside

Rethinking the Right to the City in the South

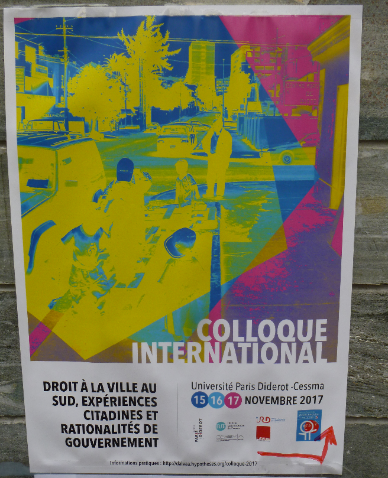

CESSMA (Centre d’Etudes en Sciences Sociales sur les Mondes Africains, Américains et Asiatiques) is leading a research consortium “Repenser le droit à la ville depuis les villes du Sud – regards croisés Afrique subsaharienne, Amérique Latine”, DALVAA in short. The research is funded by the office of the Mayor of Paris who seemed to have a particular interest in the Right to the City concept and what could be learned about the applicability of the concept in cities, such as Accra, Lomé, Maputo, Addis Ababa, Cape Town, Quito, Mexico City and Rio de Janeiro. Being in its final year, DALVAA participants searched for an exchange of ideas with the wider academic community and the inclusion of empirical perspectives beyond DALVAA research sites.

[aesop_parallax height=”750px” img=”https://blog.zef.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Paris_Irit_Eguavoen_19.jpg” parallaxbg=”fixed” captionposition=”bottom-left” lightbox=”off” floater=”on” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”none” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

The introduction of the conference came with a concise but detailed review of the conceptual Right to the City literature and a reference list which is a bit special but also very helpful for the participants. The conveners argued that two rather parallel conceptual notions of the Right to the City had evolved since the 2000s based on Lefebvre´s original writings: the revolutionary and the reformist programme.

With regard to cities in the Global South and within the development arena, the Right to the City was on the one hand taken up by international organisations (e.g. UN-HABITAT) and also by some governments and thus turned into a policy concept. On the other hand, the revolutionary aspects of the concept and its focus on social inequalities and injustices have been underlined by a number of scholars from the Global South.

[aesop_parallax height=”700px” img=”https://blog.zef.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Paris_Irit_Eguavoen_24.jpg” parallaxbg=”fixed” captionposition=”bottom-left” lightbox=”off” floater=”on” floaterposition=”left” floaterdirection=”none” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

DALVAA suggests a ´De facto Right to the City´ perspective as tool to analyse data on everyday urban practices of residents and rationalities of the government which: “aims at identifying the way city dwellers participate in the construction of a social and spatial order in the city by means of, inter alia, the daily repetition of gestures, the consolidation of social connections, the practical compliance of social rules, the means of occupying and appropriating space…” (from the DALVAA conference brochure).

Journal articles that theorise the DALVAA approach are forthcoming. The joint presentation of the concept during the conference, however, also illustrated that not all DALVAA participants were fully convinced about the theoretical framework and that internal debates will continue in the fifth year of the research. I appreciated this honesty and respect for diverse views within the group.

[aesop_image imgwidth=”100%” img=”https://blog.zef.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Paris_Irit_Eguavoen_15.jpg” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

[aesop_image imgwidth=”100%” img=”https://blog.zef.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Paris_Irit_Eguavoen_4.jpg” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

There was something else I really liked about the conference besides divergent points of view. And this was polyphony of another kind. International conferences often suggest a dominance of English that does not respect (research) realities on the ground. It was a bit more work to make sure that all participants could communicate in the lingua franca they felt most comfortable with (English, French, Spanish or Portuguese). We faced complete language barriers at times. But it gave me an idea of how many researchers might actually have been excluded from international academic discourses under English domination.

[aesop_image imgwidth=”100%” img=”https://blog.zef.de/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Paris_Irit_Eguavoen_16.jpg” align=”center” lightbox=”on” captionposition=”left” revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

[aesop_gallery id=”2435″ revealfx=”off” overlay_revealfx=”off”]

Figures: Street art on campus

Photos by I. Eguavoen

Further Reading http://www.parisrivegauche.com/Les-quartiers-et-leurs-projets/Massena-nord www.dalvaa.hypotheses.org