When nature is no longer sacred: the Sacred Mijikenda Kaya forests of Kenya

Blog by Asrat Gella, project coordinator and senior researcher at ZEF.

“I think I can smell smoke,” said one member of our research team as we entered into the sacred forests of Kaya Mudzimuvya. And she was right. Soon enough we stumbled upon what appeared to be an active charcoal making pit with logs burning inside the mound to make charcoal. Scattered all around were piles of tree trunks; trees that had stood tall in what was once a forest considered too sacred to be subjected to such practices. As we moved on, we saw further signs of destruction and even desecration; not even the sacred ancestral burial grounds were spared from the onslaught of this destruction.

It has not always been this way. In fact, just four years ago, in November 2020, UNESCO Director-General Audrey Azoulay paid a visit to this very UNESCO World Heritage; during which she pledged UNESCO’s support to protect Kenya’s sacred Mijikenda kaya forests. Despite that pledge, and despite the efforts of UNESCO and other organizations, things seem to have gotten worse.

Kaya elders walk past trees felled by illegal loggers at the Kaya Mudzimuvya Sacred Forest site; Kilifi County, Kenya.

Culture meets nature

The Sacred Mijikenda Kaya Forests consist of 10 separate forest sites, each ranging in size from 10 to 400 hectares, spread over approximately 200 km along the coastal plains of Kenya. These forest patches are remnants of what was once a continuous lowland forest that stretched along the entire Indian Ocean coast from Zanzibar in the south to Somalia in the north.

The Mijikenda people – literally the nine tribes – settled in this area in the 16th century in villages they built deep in the forests. These villages became known as kaya – literally meaning “home”. These villages, because they were located deep in the forests and because of the formidable fortifications sometimes erected around them, protected the Mijikenda people from other non-friendly tribes and, more importantly, from Arab slave traders in the 17th and 18th centuries and British colonial invaders in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Gradually, the forests around the kayas shrunk in size as the surrounding land was converted in to agricultural land – mainly for extensive sisal plantations. Starting in the first half of the 20th century, the Mijikenda began to abandon their kaya settlements within the forest, choosing instead to settle on the land that had been cleared of the forest and converted to agricultural use, and to live as subsistence farmers. By the mid 20th century, the kayas were more or less completely abandoned.

A traditional hut inside the Sacred Forest at Kaya Kauma – a symbolic reminder of what the kayas inside the forest once looked like.

However, the forests that surrounded them continued to be important spiritual sites for the Mijikenda. The forests took on a spiritual dimension and came to be revered as places of ancestral and spiritual dwelling. They became important junctions in both time and space, connecting the Mijikenda to their history, their ancestors and the supernatural spirits that were important to them.

To this day, the kaya forests are regarded by the Mijikenda people as the dwelling place of ancestors and spirits and are revered as sacred sites. Their use and conservation is governed by a council of elders. The Sacred Mijikenda Kaya Forests, thus preserved by the Mijikenda, have become important sites of cultural significance as well as biodiversity hotspots. According to some studies, Kenya’s coastal forests – of which the Mijikenda Kaya Sacred Forests are a major part – contain up to 70% of Kenya’s total plant biodiversity. Nine of these sacred forests were inscribed on the list of World Heritage Sites in 2008 and designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites of Outstanding Universal Value.

A Mijikenda elder hoists a butterfly (Kirby’s Swordtail) onto his palms inside the Sacred Forest at Kaya Kauma. The sacred forest was once a butterfly nursery. The project was abandoned as a consequence of the CoVID-19 pandemic.

The forest as a sacred entity

The protection of the natural environment of the kaya forests and their value to the Mijikenda people stems from their designation as sacred sites. The beliefs, practices, values, knowledge, and governance systems that have protected and preserved these forests have been passed down from generation to generation for more than 400 years. In the nearly half a millennium of their existence, the Mijikenda have treated the forests not just as a source of resources but as part of their very being and essence.

To be a Mijikenda was to be part of the forest. The forests were a source of the plants that the elders used for traditional medicine as well as for their healing and cleansing ceremonies. The forests are where the ancestral spirits dwell, bridging not only the present with the past, but also the physical realm with the spiritual. When times are hard for the Mijikenda, it is in the forests that the elders of the community perform ceremonies to appease the spirits and seek their protection and deliverance. This does not mean that the Mijikenda never used the forests for their needs; they did, but only to the extent of their needs and never to plunder. “We only take what we need from the forest” said Mzee Hillary Mwatsuma – the chief of the Council of Elders of Kaya Kauma. This did not allow, for example, people to exploit the forest for commercial gain and whatever was needed had to be approved by the council of elders. The forest was not a property, it was seen as a living breathing entity that could not only suffer damage, but also feel this damage, and respond unkindly to unwarranted harm.

As we poised to enter the innermost part of the Kaya Kauma forest, we were cautioned by Mzee Hillary Mwatsuma; “If you have any bad intentions for the forest, do not go any further”. Harming the forest, we were told, would come at a cost – to us. We would be haunted in our dreams, we would suffer illnesses, and we would be wise and all the better if we didn’t. These warnings along with the traditional knowledge and the code of ethics that govern forest use have largely depended on people’s self- restraint. While the Council of Elders and the spiritual leaders of the Mijikenda are charged with ensuring that the traditional regulatory systems that govern the use of the forests are respected, the system relied on the self-restraint of the people and their respect for the authority and wisdom of the elders.

There are no fences around the forests, not even boundary markers. This has undoubtedly worked well for the last 400 years or we would not see these forests today. They would have disappeared a century ago. And it is still working today in some kayas such as Kaya Kauma – which we also visited – where the forests are still largely intact and respected. But in some kayas, such as Kaya Mudzimuvya, it is no longer effective in preventing large-scale destruction of the forests. So, what has led to this? How did a sacred forest that was once revered as the place of ancestral spirits and one’s place of origin, become reduced to a mundane collection of trees just waiting to be turned into cash?

Photo left: Mzee Hillary Mwatsuma with ZEF CPC group leader PD. Dr. Eva Youkhana at Kaya Kauma.

Photo right: Kaya elders walk past trees felled by illegal loggers at the Kaya Mudzimuvya Sacred Forest site; Kilifi County, Kenya.

The decline of traditional religion and authority

Modernity has brought a decline in traditional authority systems across much of Africa and the Mijikenda have not been spared the assault on their traditional belief systems and governance structures spearheaded by an ever-growing evangelical movement. Kenya’s Kilifi County, home to five of the nine SUNESCO-registered kaya forests are found is also home to one of the biggest mega-churches in East Africa. Covering an area of 26 hectares, the New Life Prayer Center and Church in Mavueni town, Kilifi County, dominates everything else in sight. There is a one-kilometer drive from the gates of the church compound to the church; its sprawling parking lot can accommodate 2,000 vehicles; and the church’s prayer hall can host more the 40,000 congregants at a time. The church has a mansion with 31-bedroom mansion, a four-story staff quarters, a world-class hotel and restaurant, its own petrol station, luxury cottages for guests that cost up to $50 a day, a huge shopping mall, and even its own bank[1].

While they may pale in comparison to the New Life Church, the region is home to thousands of other smaller churches. This has had a significant impact on the traditional belief systems of the Mijikenda and has eroded people’s respect for the authority of elders and traditional spiritual leaders who now face increasingly vehement accusations of “witchcraft”. The younger generation is also increasingly disconnected from the traditional values of the Mijikenda and the sacred forests. Moreover, the spirits that inhabit the sacred forests are now no longer part of the “sacred” in this evangelical worldview – they are actually evil. “But they have no power over you” people are taught by the pastors of this growing Evangelical movement. If they believed in Jesus, the claim goes, they would be protected from the evils of the forest.

A partial view of the of the New Life church in Mavueni town,Kilifi County (Picture by Eva Youkhana)

Enter CoVID-19

While the erosion of traditional belief systems and authority undoubtedly paved the way and opened up the sacred forests to exploitation by removing the self-prohibitions that had been effective in preserving the forests in the past; the final blow to the forests came from a far more unlikely culprit. The first wave of forest destructions occurred after the CoVID-19 pandemic. As a result of the movement restrictions and the lockdowns put in place to contain the pandemic, many young people who had been earning their livelihoods in the nearby city of Mombasa and other coastal towns found themselves either unemployed or unable to work as the economic activity and tourism on which the region depended ground to a halt. With no jobs or means of livelihood in the cities and towns, they moved back to their home villages. There were no jobs in the villages either and with no alternative means of livelihood, they began to look to the sacred kaya forests as an untapped resource and a potential source of income.

The first axe fell on the first tree not long after that, and once that first tree was felled, it didn’t take long for the second, and the third. Within months, the trees in the outer circle of the forest, outside of the innermost sacred zone were completely gone. Given the illicit nature of the initial cutting, the trees were not felled in broad daylight in the open; there was still a degree of guilt and criminality in cutting the trees. Thus, the culprits were a few individuals, who cut a few trees into smaller logs and burned them in dirt pits to make charcoal, which they then sold. The activity was illegal, and to some extent criminal. Some were arrested, but many more were not. The illegal logging continued.

The final blow: the lifting of logging restrictions

But all that changed in 2023, when the Kenyan government led by President William Ruto, decided to lift the ban on forest logging – a ban that had been in place since 2018. As Kenya struggled to recover from the economic crisis of the post- CoViD era, youth unemployment became the government’s top priority, and opening forests to logging was seen as somehow addressing the growing discontent among the nation’s youth. “We can’t let mature trees rot in the forests while the locals suffer from lack of timber. That’s foolishness!” President Ruto is reported to have said when he announced the lifting of the ban. For the sacred forests of the Mijikenda, this was the final blow. The small-scale illegal logging that had been going on since 2020 quickly turned into a large-scale, at times even commercial, logging. Even in the Sacred Kaya forests, sites inscribed on the World Heritage List of Sites of Outstanding Universal Value, logging gained a semi-legal status as authorities either turned a blind eye to it or allowed it to continue. Some local authorities, including Members of Parliament, are even said to be complicit in the logging – encouraging unemployed youth to make a living by exploiting forest resources; and even fencing off large tracts of land within the forests for their own use.

ZEF CPC “Local Dynamics” project researchers Dr. Erik Kioko (left) and Dr. Muthio Nzau (middle) discuss sacred forests with a Mijikenda elder; Kaya Rabai, Kilifi Conty – Kenya

Large-scale quarrying near forests

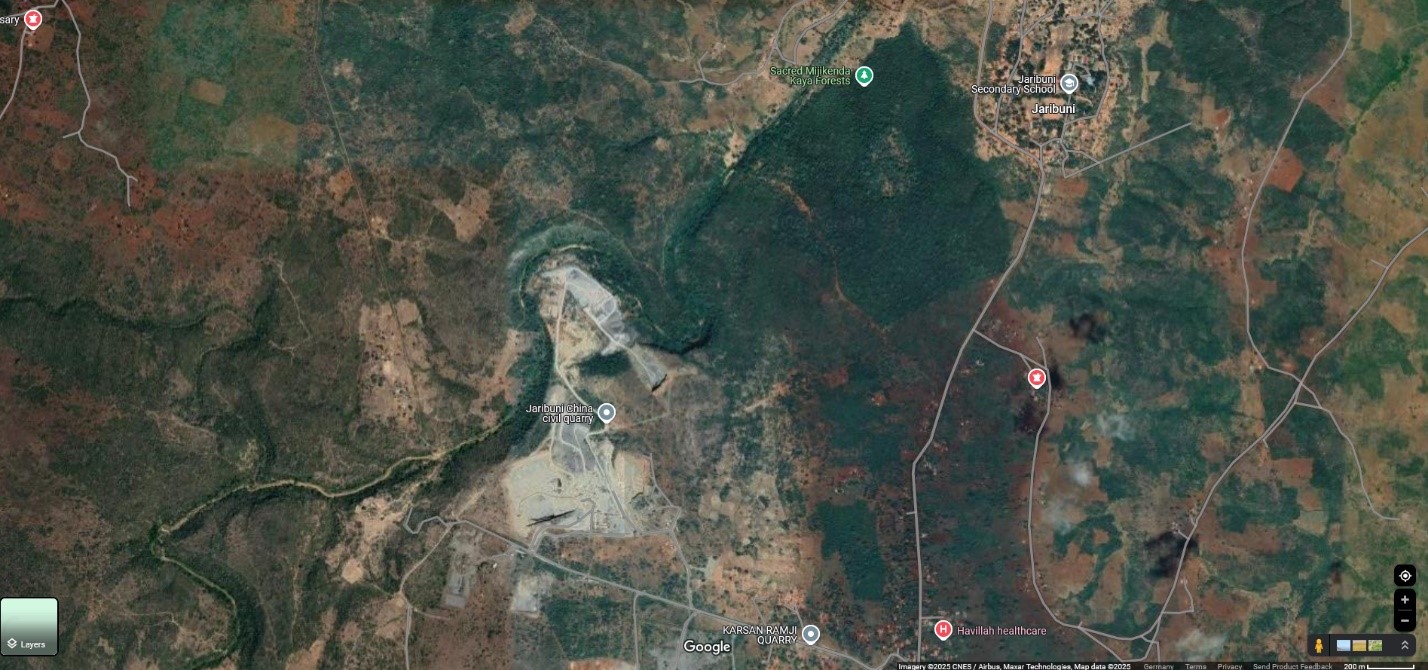

Yet another threat to the sacred forests has emerged from extensive quarrying. The sacred forests of Kaya Kauma are among the best preserved of the Mijikenda Kaya forests. Unlike the sacred forests of Rabai, which have suffered from extensive logging over the past two years, the forest at Kaya Kauma is largely intact and contains several baobab trees that elders estimate to be at least two centuries old. Here, the threat to the forest comes from small-scale iron ore mining by local people and a large-scale quarrying by more than 16 companies operating at a quarry site near Kaya Kauma –including the giant Chinese state-owned China Civil Engineering Construction Corporation (CCECC) which is building the largest transport corridor in the East Africa region, linking Kenya with Ethiopia and South Sudan. In addition to the forest encroachment, pollution from the quarry site pollutes the forest and the nearby river, thereby threatening the health and integrity of the forest ecosystem.

Large-scale quarrying near the Sacred Mijikenda Kaya forests at Kaya Kauma; (photo left: Google earth satellite image; photo right: taken at the site in December 2024)

Uncertain futures

The outlook for the Sacred forests of the Mijikenda does not look great. Some, such as the forests of Kaya Rabai are already on the verge of disappearing altogether already. Others are under enormous pressures from extractive industries and land grabs. There are inter-generational tensions and disagreements between the elders and youth about the very nature and meaning of the forests themselves. Where the elders see history and sacredness, the younger generation sees resources – whether that be in the form of trees, land, or iron ore – to which they feel entitled as members of the Mijikenda community and as citizens.

These disagreements have led to open hostilities with disenfranchised youth destroying tree nurseries and even burning community centers in retaliation for facing legal and social consequences as a result of their alleged involvement in logging. There are also a host of other external actors ranging from real-estate developers to commercial farms and miners who see as the sacred forests as in their way, and are blocking them from staking a claim to the land. All of this has made the future of the Mijikenda sacred forests extremely precarious. The ZEF CPC “Local Dynamics” research project, funded by the Volkswagen Foundation, is working to understand these local dynamics in the UNESCO inscribed cultural landscapes and their implications for the continuously evolving and changing nature of cultural landscapes as “living” landscapes.

Background info and credits

This blog post is part of an ongoing research project Local Dynamics and Integration of UNESCO World Heritage Sites of Outstanding Universal Value: Evidence from Cultural Landscapes in Ethiopia and Kenya. The project aims to understand UNESCO World Heritage Sites as “living landscapes” that are shaped and transformed through local dynamics including context-specific socio-economic, cultural, environmental, and political factors. The project is a collaboration between ZEF’s CPC research group, Dilla University in Dilla, South Ethiopia, and Kenyatta University in Juja, Kenya.

All pictures by Asrat Gella unless specified otherwise.

[1]Source: https://www.standardmedia.co.ke/health/features/article/2001472285/inside-pastor-ezekiels-new-life-prayer-centre-and-church